Kamakura Rediscovered - Omachi and Zaimokuza

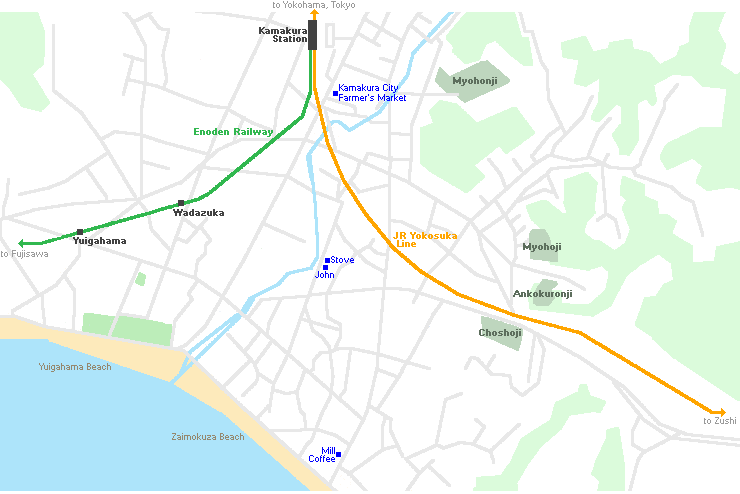

Rounding off my six part series delving into the historic city of Kamakura one neighborhood at a time, I recently spent a hugely enjoyable day exploring the southeastern part of the city, from Kamakura Station to one of the city's most attractive stretches of beach, taking in the two districts of Omachi and Zaimokuza.

On the day of my visit, weather was very warm and humid, but despite occasional flashes of sunlight the sky was largely overcast and darkening clouds threatened rain later in the day.

Setting off from Kamakura Station's east exit, I turned onto Wakamiya Oji and headed south towards the beach. After a few blocks, I arrived at the Kamakura City Farmer's Market, or Rembai as is known locally - a single story concrete building with an open space for market sellers and a handful of small shops. It may not look like much, but if the foodie community in this part of town has a heart, this may be it - and ever since I first began exploring the city, friends have been urging me to come and see it.

Stepping inside the market area, I found rows of trestle tables loaded with fresh vegetables and other produce, and a lively atmosphere as locals make their way around shopping and chatting to vendors.

Of the few small shops connected to the market, two especially worth a visit are Paradise Alley Bakery, one of Kamakura's most celebrated bakeries known for experimenting with leaveners and other ingredients of all kinds, and Long Track Foods, a tiny but very welcoming little store offering a range of locally made snacks and cooking ingredients. I can highly recommend their ice cream sandwiches!

From the market, I crossed the Nameri River and made my way east to Chokozan Myohonji, one of several historic Buddhist temples in the area with a strong connection to the 13th century priest and philosopher Nichiren.

A fiery and sometimes controversial figure, Nichiren arrived in Kamakura in 1253 at a time of political upheaval and natural disasters. Already with a reputation for apocalyptic predictions and fierce attacks on his many rivals, his passionate sermons soon began to attract a devoted following of disciples.

One such follower was Hiki Yoshimoto, the last surviving member of a once-powerful samurai family, said to have converted on the spot upon hearing Nichiren preaching on a Kamakura street. At the beginning of the 13th century, Yoshimoto's father Yoshikazu had been a close ally and father-in-law to the young Shogun Minamoto no Yoriie, while political power lay with the Hojo family as hereditary regents. When Yoriie fell seriously ill, he made secret plans for his son to succeed him with Yoshikazu serving as regent, cutting the Hojo out of power.

Tragically for the Hiki clan, the Hojo soon became aware of the plot and responded immediately - luring Yoshikazu to his death under cover of peace talks, then launching a surprise attack on the family residence, burning it to the ground.

Upon becoming Nichirenfs disciple, Yoshimoto had a temple built here on his ancestral land, not far from the site of the destroyed family residence, to console the spirits of the dead.

Today, the temple is best known for its large main hall, called the Soshido, which is around 170 years old and whose main object of worship is a wooden statue of Nichiren carved in the 14th century.

Several clues to the Hiki familyfs tragic history can still be found within the temple grounds, none more poignant than the grave of Yoriie's infant son, Ichiman. The spot is known locally as the Sodezuka or sleeve mound, as fragments of kimono sleeve were said to be the only trace of the boy found in the ashes of the family residence.

A short walk to the southeast, I arrived at Ankokuronji, one of three temples in an area once called Matsubagayatsu, or the Pine Needle Valley, all with a strong historical connection to Nichiren.

Somewhere in the valley is the spot where the famous priest secreted himself in a hut to write a tract called Rissho Ankoku Ron, published in 1260 - a typically fiery text that would bring fame and notoriety to his burgeoning movement, and from which the temple takes its name. Exactly where the hut was located, however - and in which of the three temple grounds - has been the subject of much dispute.

Passing through the elegant front gate, I found myself in a narrow path lined with cultivated moss and tall trees. There was no-one manning the gate, so I duly dropped a hundred-yen piece into a wooden box beside a tall stone lantern that once stood in Zojoji Temple, Tokyo.

Up ahead the garden opened up and I arrived at the main hall, which dates to 1958 having been rebuilt after a fire.

Behind me and to my right I found the Goshoan or small hermitage, built on the site where Nichiren is said to have written the Rissho Ankoku Ron. The tall tree that stands in front is said to have been planted by Nichiren himself with a seed brought from his native Awa Province, part of today's Chiba Prefecture.

Beside the Goshoan, I took a flight of narrow stone steps up the hillside to the Fujimidai - a viewing spot offering a sweeping view across the city and as far as Mount Fuji on a clear day.

The path continued for a while along the ridgeline before looping back towards the temple entrance, passing a bell of peace and a small cave where Nichiren is said to have taken up residence when his small hut burned down.

Just around the corner, I made a brief stop at Myohoji - another small temple whose origins reflect the political intrigue, tragedy and interconnectedness of Kamakura's history.

Myohonji's first abbot, who took the name Nichiei, was the son of the executed Prince Morinaga and a court lady, conceived during the prince's imprisonment at what is now Kamakura-Gu Shrine. Today, the little temple is best known for a long flight of mossy stone steps leading to the prince's cenotaph, earning it the local nickname Kokedera, or moss temple. Sadly, these are off limits today so I content myself with a look at its main building and attractive, rather overgrown garden.

From Myohoji, I began to make my way southwest towards the coast, but by then I had started to work up an appetite, so decided to make a stop at Mill Coffee & Stand, a delightfully cozy little cafe located just a couple of minutes' walk from the beach. Here, I enjoyed a beautifully prepared cup of coffee and perhaps the best pastrami sandwich I've ever had in Japan.

Just around the corner from Mill Coffee, I finally arrived at Zaimokuza Beach, one of Kamakura's most attractive stretches of sandy beach and a haven for surfers, windsurfers and stand-up-paddle-boarders. Due to the threat of coronavirus, the beach remains closed this year, so there were none of the vendors one would see in a typical summer season, and little of the crowds. Despite this however, a few surfers were still out enjoying the waves.

Finding a nice spot, I paused for a few minutes to enjoy the uninterrupted view as far as Imamuragasaki, and a last few rays of sunshine before the weather took a final, decisive turn for the worse.

With the skies beginning to open, I threaded my way back through quiet residential streets for my final stop at John, a cafe and gallery set in a renovated older building.

The owner, Yuriko-san, moved to the area with her husband around ten years ago in search of a more laid-back atmosphere, and to be near the sea.

As well as its elliptical name, the cafe is known for excellent coffee and cakes, both produced by small, independent businesses, adding to an appealing sense of community and collaboration.

While sheltering from the rain, I enjoyed an iced coffee and a slice of plum cake so delicious it left me quite lost for words.

Taking a look at the attached exhibition space, I met Zushi-based artist Machida Hirochika on the final day of a solo exhibition, with a series of lively, colorful works inspired by the local area.

Just next door, I happened to meet Jun-san, the other half of the husband-and-wife team, at his own store called Stove - an eclectic mix of handmade furniture, crafts and camping gear set in another attractively renovated townhouse. Drawing on their experience at a Tokyo-based interior design company, the couple were able to carry out much of the renovation work themselves, giving the space an understated but stylish look.

With a last look at the various pieces on display, my day in Kamakura was coming to an end and it was once again time to make my way back to the station, reflecting on all that I'd experienced in the city in the course of the last few months.