Four spots not to miss on the Boso Peninsula

Located within just a couple of hours' journey by train from Tokyo, the Boso Peninsula is a large body of land forming roughly the lower half of Chiba Prefecture - a peacefully rural area of forest, fields and rolling hills hemmed in on three sides by the windswept Pacific coast. Already a popular getaway for Tokyo residents, the peninsula as a whole continues to fly under the radar of most international visitors, making it a great place to avoid the crowds.

For all its understated rural charm and slower pace of life however, the area offers a great deal of cultural depth and plenty to see and do. Where my previous article covered recommended accommodation in the Kamogawa and Kujukuri areas, here I'll explore just a handful of the peninsula's best activities and sightseeing spots.

Rising to just 329 meters at its highest point, Mount Nokogiri may be a small mountain yet it still towers over the surrounding landscape, running east to west between the two coastal towns of Kyonan and Futtsu. Unusually long and straight, its ridgeline tapers sharply into a narrow and slightly jagged edge, long ago earning the mountain its name, meaning "sawblade" - the effect made even more prominent by deep striations in the rock from centuries of quarrying.

While I chose to make my way to the foot of the mountain by rental car, it can also be accessed in about two and a half hours from Tokyo Station to Hama-Kanaya via the Sobu and Uchibo lines, with one easy change at Kimitsu.

Together with Aragaki-san - my guide for the day from specialist local company WEGUIDE Nokogiriyama - I set off from a parking lot in neighboring Kyonan on a fairly relaxed three-hour hike taking in some of the mountain's best-known sights and viewing spots. Soon chatting away easily in English about the surrounding landscape and its long history, we turned onto an old sando or temple approach before slipping through the treeline and onto a worn mountain path.

At the heart of the mountain is Nihonji, an ancient temple founded all the way back in 725 by Emperor Shomu. Dedicated from the beginning to Yakushi Nyorai - a buddha associated mainly with medicine - it was intended to protect the people from epidemics that plagued the country in those times. Over the course of a rather tangled history, it would change its affiliation several times before settling on the Soto Zen school of Buddhism in 1647.

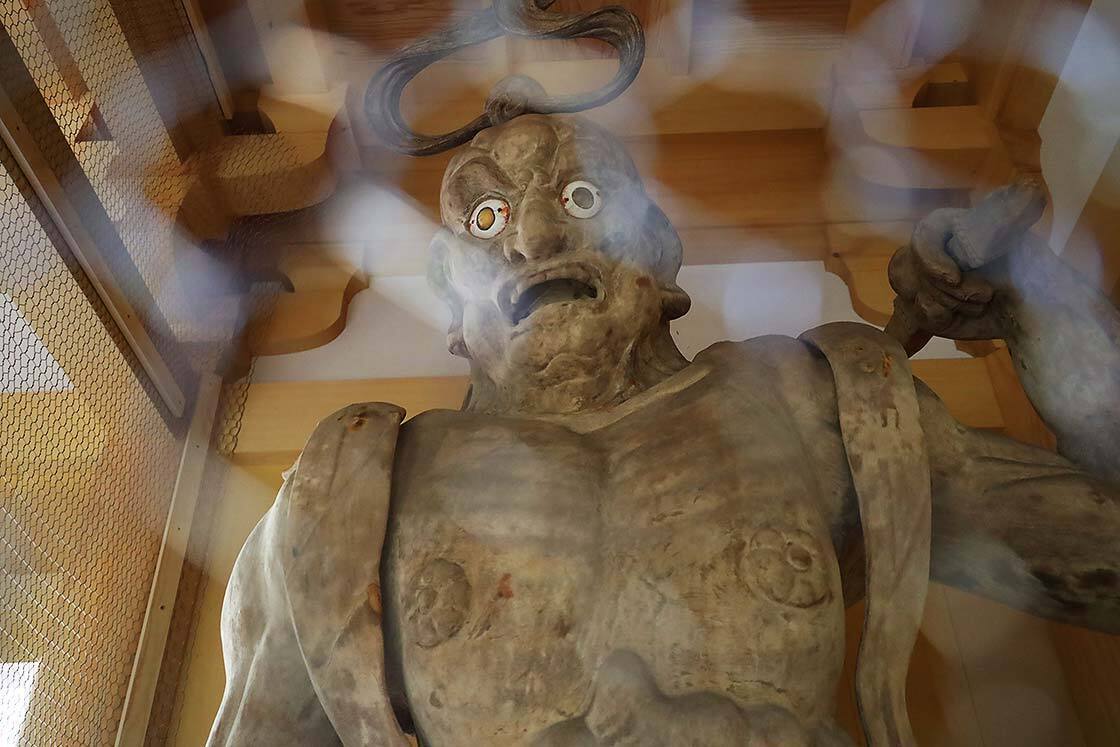

Arriving at the limits of the temple grounds, we passed by two brand new structures completed in the summer of 2025 and still cloaked in the clean, tangy scent of Japanese cypress - a niomon gate with its two towering guardian figures, and the Kannondo.

Just a little further ahead, we arrived at the main part of the temple complex, including a wide main building, bell tower and ornate three-storied pagoda. While the current buildings were completed as recently as 2025, this central part has stood here since 1774, when the high priest at the time relocated many of Nihonji's buildings from the foot of the mountain. Throughout its history, the temple would be abandoned and rebuilt numerous times.

His decision to do so was likely not just a spiritual one, but highly practical - greatly enhancing the temple's reputation and drawing pilgrims from far and wide. Visitors naturally needed food, lodgings, offerings to make and even souvenirs to take home, so the benefits would also have trickled down into local communities.

A little way uphill from the main building, we came to a fascinating structure hewn directly into a rock wall, the first of many clues to the mountain's importance as a quarry. Known as the Tsutenkutsu, or Cave of Passing to Heaven, it was made to resemble a small temple complete with pillars and an elegantly gabled roof, and enshrines the Edo Period Zen master Kogaguden.

Breathing a little harder as the path began to turn more steeply upward, we started to notice clusters of little statues tucked away in carved grottoes, each one of what appeared to be a monk or mendicant priest rendered in a huge variety of poses and expressions. These are called rakan - traditional depictions of those who have reached a personal level of enlightenment - and, counting all of Nihonji's 1,553 original examples together, the largest collection of them in all of Japan.

Every one of the original pieces was carved with its own unique features, pose and expression - my guide mentioned a local saying that every visitor finds one they seem to recognise - and were made under the supervision of a single master stonemason. Today, little is known about Ono Jingoro Hidenori, except that he was born in 1750 in what is today Kisarazu City in Chiba Prefecture. No major works of his survive outside of Nihonji, yet he must have had a formidable reputation to be given such a mammoth task. Even with a team of 27 disciples, the work is said to have taken 21 years to complete.

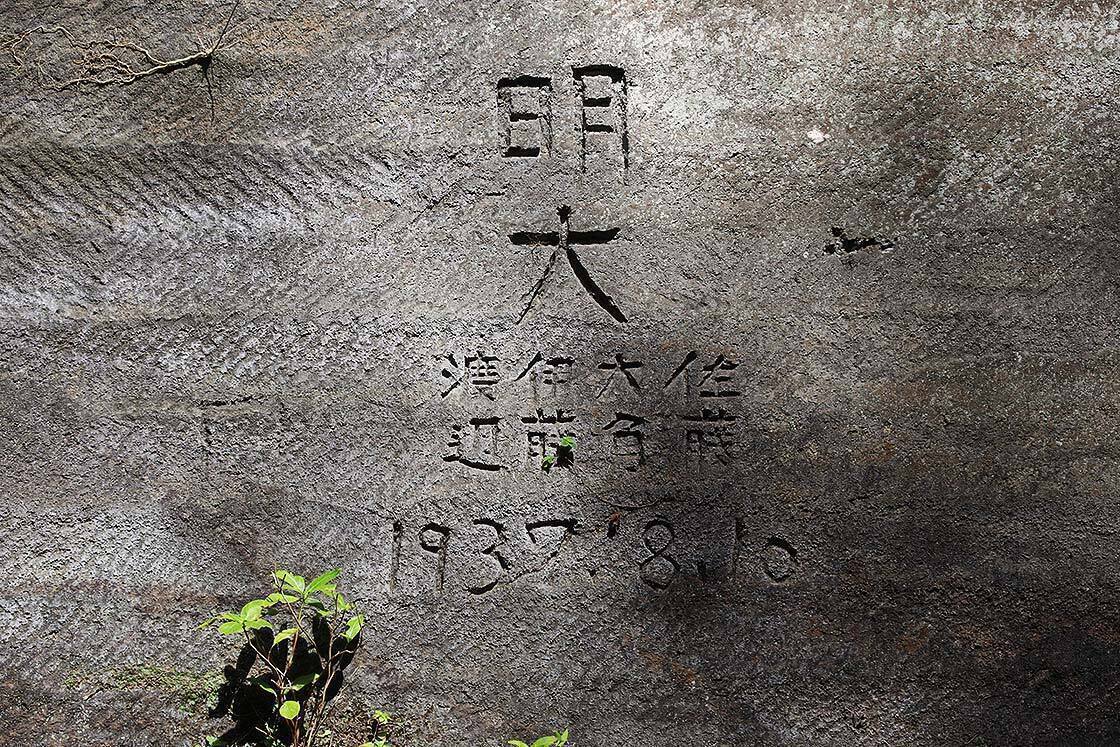

Already the site of sporadic stone-cutting by the 15th and 16th centuries, the mountain began to be much more intensely quarried from the Edo Period onwards, producing a distinct local stone called Boshu-ishi. Occupying a certain sweet spot between ease of cutting and structural strength, it was perfectly suited to large-scale construction projects and was widely used throughout the Tokyo Bay area.

Work on the mountain was carried out for the most part by local family businesses, with women playing a crucial role in bringing the cut stone back down the mountain, often along crude pathways called shariki michi, or stonecutter's roads. The advent of mechanization and industrial cableways would eventually transform the process, but for generations all moving was done under human power.

By the 1960s, demand for large natural blocks had waned in favor of concrete and stonecutting on the mountain soon wound down to nothing, leaving its many exposed quarries eerily empty. Around the same time, Nihonji commissioned the first of two spectacular large-scale sculptures in one such quarry close to the summit.

Standing at just over 30 meters in height, the Hyakushaku Kannon or "100 shaku Kannon" is one of Japan's largest standing relief statues, depicts the bodhisattva of mercy in a serene attitude and is dedicated to those killed in accidents, wars and natural disasters. Approaching from a long stone-cut passageway, my first glimpse of it came just as I was rounding a corner, creating a dramatic reveal.

Just a couple of minutes' climb from the statue is another of the mountain's most famous spots, the Jigoku Nozoki - a dramatically overhanging rock ledge with a breathtaking view across the Tokyo Bay and back along the peninsula's east coast.

A slight haze reduced the distant form of Mount Fuji to only a faint outline, but I could clearly make out Yokosuka City on the opposite shore and even a shimmer of glass and steel on the Tokyo side.

Now on the descent, we passed more grottoes packed with rakan statues and the occasional trace of long-dismantled temple buildings on our way to one last highlight - the Nihonji Daibutsu or great Buddha statue. Begun in 1783 by Ono Jingoro Hidenori and never completed, the statue's original form is said to have comprised only the part of the body from the head to the hands. By the mid-20th century however its form had weathered almost beyond recognition.

In 1969, a project to restore and expand the original to include the Buddha's lower half, while a much smaller seated Buddha - originally in the palm of the Daibutsu's hand - was relocated above its head, where it now joins a halo of seven such figures. At 31 meters, it is just over twice the size of the bronze daibutsu at Todaiji Temple in Nara and exudes a strikingly serene aura.

My guided climb was a great start to my time on the Boso Peninsula for a couple of reasons - the combination of some local lore and those sweeping views along the coast really added to my sense of place and helped me to put other cultural tidbits into context, and while often underrated, just having a friendly face to welcome you to a new place for the first time can make a huge difference to your first impression. For information on how to book, take a look online.

Back at ground level, I said goodbye to my guide took a five-minute drive down the coast to Kyonan's Hota Port, a sheltered fishing harbor with boats of many shapes and sizes moored in neat rows. Here, I refueled after my steep and sweaty climb with a generous seafood lunch at Ban-ya Honkan. The older and more casual of two Banya establishments at the port along with the more upscale Shinkan, the Honkan perfectly matches its surroundings with an unfussy, traditional feel and a broad menu of local favorites to choose from.

I started off with a mixed sushi set including lean tuna, sea bream, yellow amberjack and crunchy, clean-tasting whelk. Not surprisingly for a restaurant mere steps from the water's edge, everything was incredibly fresh and flavorsome, and I soon followed it up with a plate of namero - a signature Boso fisherman's dish with minced and seasoned sashimi formed into a pâté-like mixture. Typically made from horse mackerel, it has a slightly oilier mouthfeel than most sashimi, while a touch of ginger and shiso in the seasoning adds a bright, spicy note to the flavor.

For my next two experiences, I took a 30-minute drive southeast into the peninsula's interior, passing wide open fields and rustic terraced rice paddies on my way to Yamana, a sleepy neighborhood on the rural outskirts of Minamiboso City. By public transport, one would need to take a 25-minute ride down the coast from Hama-Kanaya Station to Nakofunakata, followed by a 20-minute journey by bus.

My destination here was a lovely 300 year old traditional farmhouse today known as Yamana House, preserved and repurposed by the Satoyama Renovation Project as a center for activities such as forest walks, wildlife education and - as I was about to take part in - sustainable cooking experiences.

My host for the day was Yumiko-san, a community guide and lead organizer at the house, known for her deep knowledge of the local environment and her commitment to making connections between visitors and the traditional Japanese countryside lifestyle. Friendly and approachable, I was also impressed to find her looking perfectly composed in a beautiful three-layered kimono despite the early autumn heat.

My first experience - which can be booked here - involved learning how to make yuzu kosho, a traditional condiment originally from Kyushu but hugely popular throughout Japan. Created from just three ingredients - fresh green chillies, yuzu zest and salt - just a dab of the stuff adds a potent citrus-spicy kick to just about anything, from soups and hotpots to grilled meat and fish.

With the ingredients already prepared, the steps to making it were both simple and enormously satisfying - thinly slicing handfuls of the peppers and yuzu peel into a tangy-smelling paste and slipping it into a jar with a drizzle of salt mixed in. This would disappear into a fridge to ferment for up to a year, helping to soften the fire and acidity, while adding additional richness and complexity - perfect for winter dishes.

With the yuzu kosho put aside, it was time for something I'd been looking forward to since arriving on the peninsula - a jibie or wild game barbecue served in the open air with locally vegetables, not to mention a whole range of delicious-smelling rubs and sauces devised by Yumiko-san herself.

Even for someone like me who has had far more than their fair share of barbecues, what came next was nothing short of dazzling - a succession of beautifully prepared meat and vegetable dishes, from locally-caught venison neck and wild boar loin to peppers, aubergine and tomatoes fresh from the garden, the latter stewed in a skillet with rosemary from Yamana House's own herb garden.

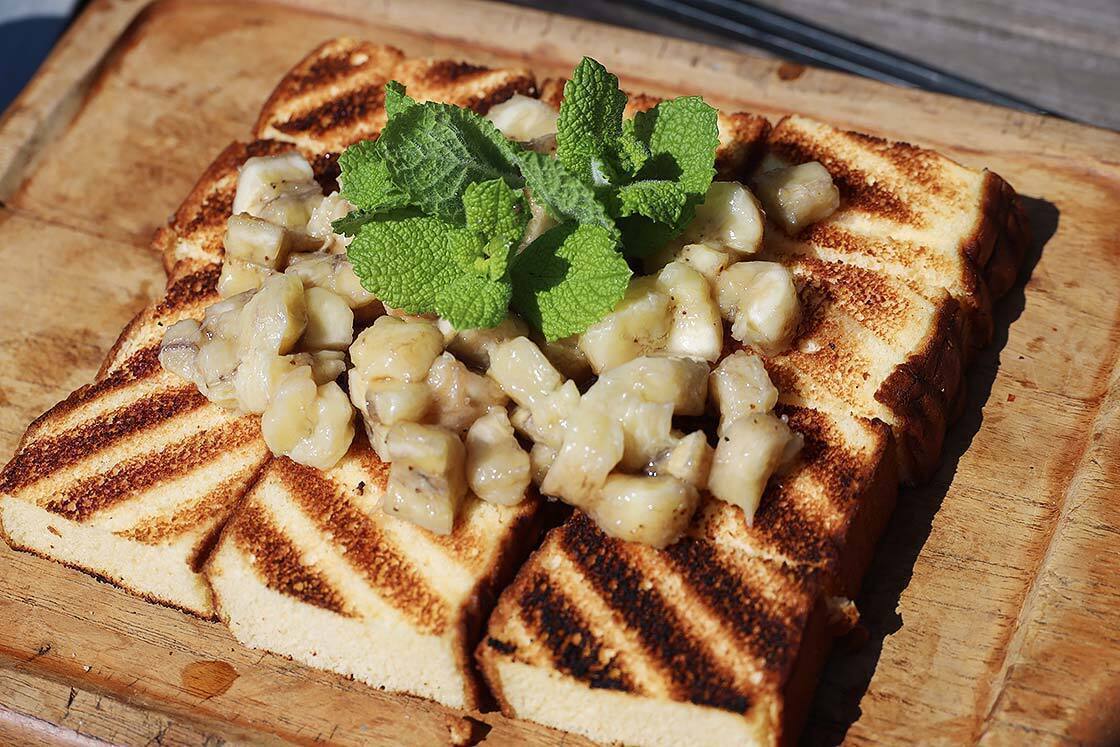

The combination of so much wonderful food with the warm country air, all while chatting away about local farming culture, hunting and the experience of living in such a quiet and beautiful area, all added up to something really special - for details of how to book, check online. After one last dish though - homemade castella topped with mint and barbecued banana - it was time to say my goodbyes and continue on my way.

My next stop lay 30 minutes' drive to the south at the very tip of the Boso Peninsula - the Nojimasaki Lighthouse. The second oldest western-style lighthouse in all of Japan, it was one of eight built during the early Meiji Period (1868-1912) as part of the country's efforts at modernization. Today, it is also one of just a handful that can be climbed, offering a spectacular view out to sea that on clear days reaches as far as Izu Oshima, 61 kilometers out to the southwest.

My time on the peninsula was almost at an end, but I was keen to make one final stop, another 30 minutes' drive along the east coast in Tateyama City. Here, clinging to a sheer cliff face on the side of Mount Funakata is the Gake Kannon Hall of Daifukuji Temple - one of the best-loved and most distinctive Buddhist buildings in Chiba Prefecture.

Traditionally, the temple is said to date to 717 when a priest named Gyoki carved an image of Kannon in her eleven-headed aspect into the cliff wall. Many years later, a hall was built around the sculpture with a stage-like balcony overlooking the Tateyama Bay. Over the centuries, a combination of harsh sea air, earthquakes and general deterioration took a heavy toll, requiring near-constant repair. The current structure dates to about 1925, and visitors may still be able to catch a glimpse of the original carving through a heavy grate that guards the altar.