The cutting edge of traditional kitchenware

Last year, I spent a fascinating and thoroughly enjoyable day visiting the three Tokyo branches of MUSASHI JAPAN - an up-and-coming knife brand making waves with its innovative and highly accessible approach. Seeing its staff in action, I found a lot to like about the company, from its solid product line to the staff themselves - bright, articulate, with an easy and infectious enthusiasm. Perhaps best of all - at a time when visitor numbers are at an all time high but many traditional crafts are in decline - it was great to see a company being so proactive in making a case for one of Japan's heritage industries.

With the company recently opening three new branches in Kyoto - Japan's former capital and for many, still the heart of its traditional culture - I decided to make another visit while also highlighting some other shops and ateliers, each with their own special place in the city's legendary craft scene. Whether you're looking to delve into the world of traditional crafts or just find your own authentic piece of Japanese culture to bring home with you, here are five fascinating spots in Kyoto to start with:

Zohiko

Believed to date back as far as the Jomon Period (13000 BC to 300 BC), the art of Japanese lacquerware or shikki is an ancient one with deep connections in Kyoto. At its core, it can be summed up as the art of painting wooden or sometimes paper items with urushi - a product of tree sap - adding durability and water resistance, as well as a beautiful color and sheen. The surface may be further decorated by sprinkling gold or silver powder onto the wet lacquer (maki-e), or by inserting inlays of abalone or mother-of-pearl (raden).

Kyoto became a major center for the craft during the Heian Period (794-1185), with the refined tastes of the imperial court driving demand for finely decorated boxes, vessels and ritual objects. Later, the development and formalization of the tea ceremony from the 14th to the 16th centuries would also have a major impact on the aesthetics of the city, while a whole new category of arts and crafts formed around its ritualized instruments.

One of Kyoto's oldest and most respected makers of lacquerware, Zohiko began in 1661 when its founder, Hikobei Nishimura I, inherited a Chinese-import goods business and developed it into a specialty shop for lacquerware. Since then, successive generations of owners have inherited the name "Hikobei" and dedicated themselves to preserving the brand's legacy of exceptional lacquerware craftsmanship.

Located in the Marutamachi area of central Kyoto, Zohiko's main store today offers a wide range of products, from the highly ornate writing boxes that have been a signature of the brand for centuries to fashionable home goods.

Kanaamitsuji

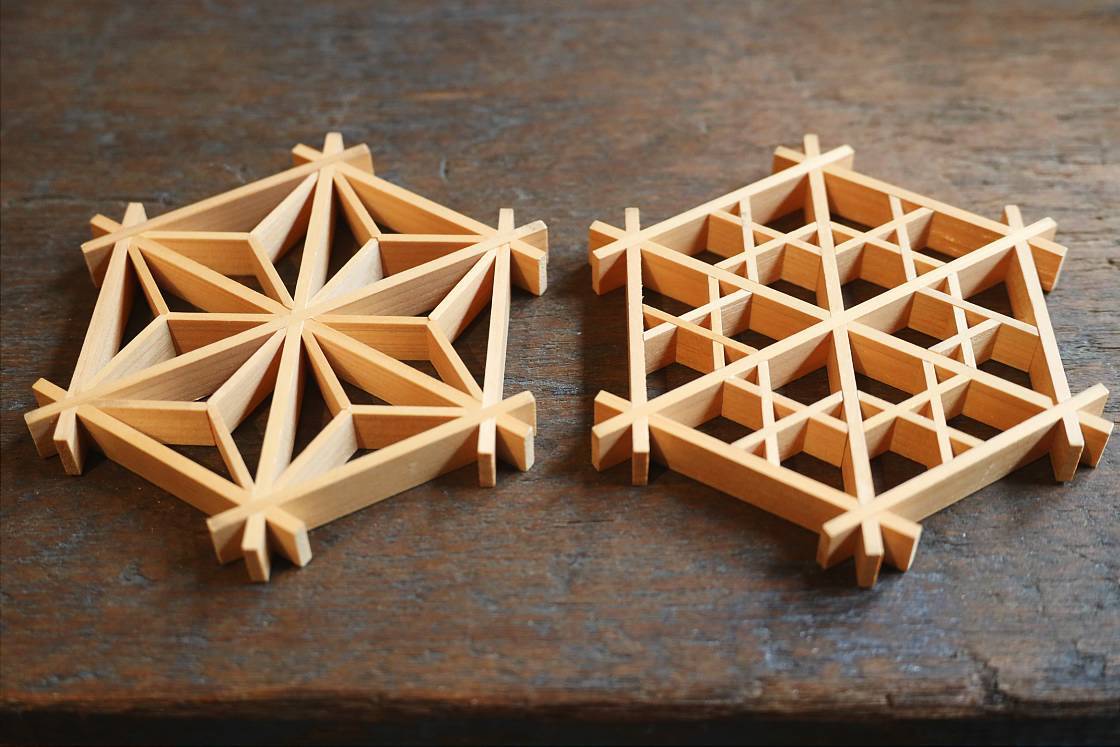

Said to have originated in Kyoto over a thousand years ago, kyo-kanaami is the art of weaving metal wire into a delicate and finely patterned mesh, originally used to create cooking utensils, decorative elements in temples and shrines, and incense tools for the nobility. One of just a handful of workshops preserving this artform today, Kanaamitsuji is working to preserve its notoriously exacting techniques while evolving its forms to appeal to a modern sensibility.

With everything created painstakingly by hand, a single product can take hours to complete placing great demands on the artisan. While a machine would be many times faster, doing it this way allows for a smooth, unblemished finish and the use of intricate patterns like kiku-dashi (chrysanthemum) or kikko-ami (tortoiseshell).

As a child, Tsuji Toru saw firsthand the demands of the artform on his parents and resisted following in their footsteps, choosing instead to work in fashion and travel abroad for a few years before having a change of heart in his early twenties. Now the head of the family, he has since traveled to various other countries in search of inspiration and expanded their product line to include more modern items like lampshades and even jewelry.

Today, visitors to Kanaamitsuji's attractive little shop in the popular Higashiyama district can browse a range of unique items, watch one of its craftspeople at work or even try their own hand at the traditional techniques at one of its hands-on-workshops, available to book on request.

POJ Studio

Located inside a 100-year-old renovated townhouse just a short walk from the Kyoto National Museum, the third spot on my list is not a workshop per se but a store offering a selection of curated crafts, from pottery and lacquerware to less recognizable items like Buddhist singing bowls or elaborately braided hempen rope.

Beginning as an online-only business just before the coronavirus pandemic began to take hold in Japan, POJ Studio's first product was not a handcrafted item at all but a kintsugi restoration kit - born of a desire not just to promote consumption but rather to actively support the craft ecosystem in thoughtful ways. As cofounder Tina Koyama explains: "People were at home, shopping online, with time on their hands - and what we offered just happened to resonate: a meaningful, hands-on way to connect with storied pieces and bring them back to life."

Since then, the company has only gone from strength to strength, with an expanded catalogue of products rooted in lasting relationships with craftspeople. "First and foremost, we care deeply about the craftspeople and what they want to achieve," Ms Koyama explains. "When we're introduced to someone new, we rarely come in with fixed ideas. Instead, we approach each relationship with a problem-solving mindset - asking what they hope to create, where they see themselves in the future, and how we can support that vision."

&restaurant Kotowari

Testament to the power of friendship, shared vision and clever utilization of space, this uniquely named restaurant and atelier is a collaboration between Chef Shimizu Hiroki, a 20-year industry veteran, and his long standing friend Akashi Shinichi, owner of a family-run leather goods business. Together, they set out to create a one-of-a-kind coworking space with a relaxed atmosphere, where customers can enjoy a meal while browsing goods on display or even waiting for a repair.

While the lunch menu is heavily influenced by obanzai - a subset of Kyoto cuisine emphasizing the kind of simple yet highly seasonal and beautifully presented meals one's mother might make at home - the dinner service reverts to something more like elevated izakaya or pub food. Despite, or perhaps because of the chef's many years of experience, the restaurant has been dubbed "sosaku", or "creative", meaning that it emphasizes artistry and innovation over strict adherence to traditional recipes.

Arriving in the evening, I ordered plates of mixed sashimi, salad and nerimono - a kind of kneaded white fish paste, shaped into hollow cylinders then chopped and deep fried - finishing with a rich and meaty sukiyaki hotpot. Perfectly matching the space's casual vibe, the food was hearty, delicious and left me wanting to learn more about how it was made.

MUSASHI JAPAN Kyoto Sanjo Store

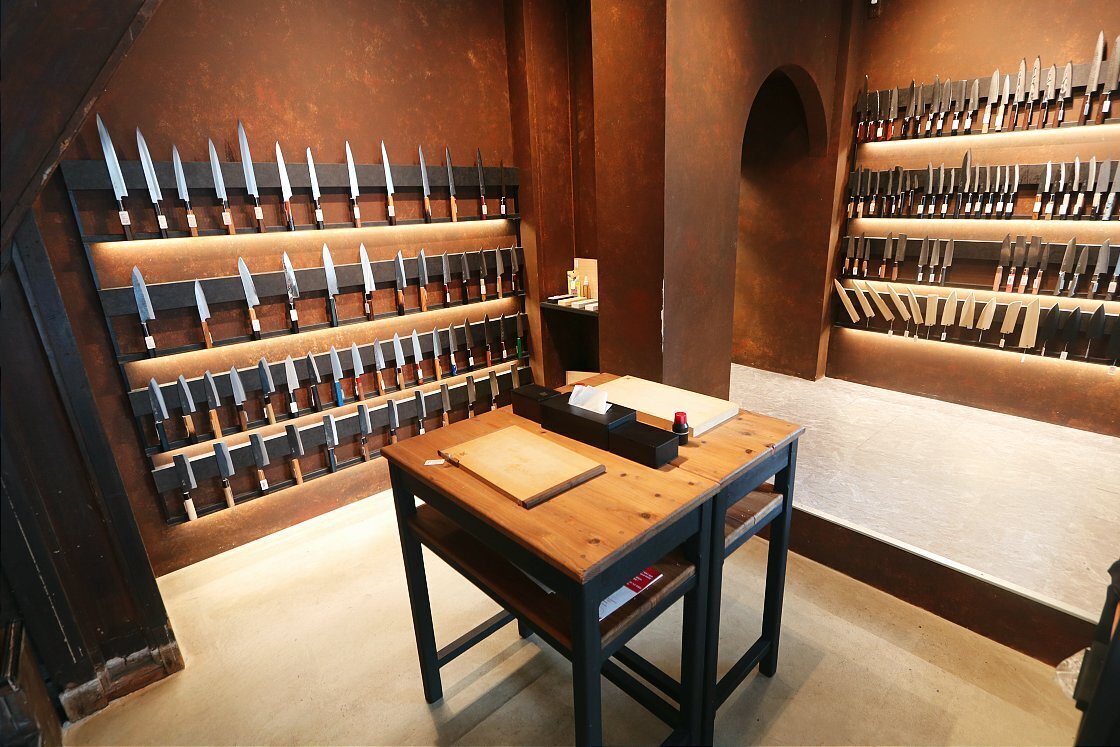

Located just a short walk from Nijo Castle along the Sanjo Meitengai - one of the city's oldest shopping arcades - MUSASHI JAPAN's Kyoto Sanjo branch is instantly recognizable from its sign, the familiar rows of sharp, glinting steel and a stylish, textured design resembling tsuchime patterning.

Making my way inside, I first spent a few minutes getting to know the staff - a typically bright and friendly bunch with multiple languages between them as well as an impressive amount of knife-related knowledge. First to shake my hand was Clement - a softly spoken Belgian man who joined the company straight out of college after completing a degree in Japanese.

While every employee I met had a different story, it's clear that this is a company that chooses its people carefully, and not just to make it a nicer place to work and shop. In fact, it's a key component in Musashi's strategy - a visit to one of their stores becomes a learning experience, adding a real sense of value and appreciation for the customer.

Just as important to Musashi's success is its relationship with expert knife-makers from all over Japan, from legacy brands like Yoshikane in Niigata Prefecture to up and comers like Nakagawa Satoshi - the youngest person ever to be craft certified in his native city of Sakai, Osaka.

A year on from my last visit and already a little bit rusty on some of the basics, I was keen to start with a refresher on the various kinds of traditional Japanese knives and their different functions. First up was the deba - a thick, heavy blade with a single edge and pointed tip, used for breaking down and filleting fish. The second and, at least to me the most eye-catching, was the yanagiba or willow blade - a long, supple knife designed just to cut thin strips of sashimi in a single motion.

While most of the knives on display shared a kind of sleek, stripped-back elegance, several of the unique signature ranges stood out thanks to eye-catching details that seemed to cry out to be looked at again and again. This was especially true of a series by Takao Asamura, a Chiba-based master of chokin or gold engraving, each blade decorated with traditional motifs carved in a delicate hand and finished with 24 karat gold.

Others impressed with beautiful handles, like a range by Fujiwara Akihiro made with brightly colored buffalo turquoise, or the Tsushima Ocean Knife line fashioned from recycled plastic - sea pollution being a major issue facing communities on Japan's coasts and smaller islands.

Another striking feature found in a number of Musashi's blades is a distinctive wavy, crystalline pattern in the grain - something I had seen elsewhere described as "Damascus steel". As Clement explained, this is actually a bit of a misnomer as the technique behind real, historic Damascus steel has been long since lost to history, but there is far more to it than mere decoration.

An indicator of high quality construction and great skill on the part of the maker, such patterning is typically achieved by laminating multiple layers of steel, with a hard inner core for sharpness sandwiched between stainless or high carbon layers for toughness and corrosion resistance. Revealed only gradually by repeated folding, hammering and etching, the Damascus-style waves recall similar patterns in Japanese sword making and are even said to reduce friction, so that ingredients are less likely to stick to the blade when chopping.

Of course, even a world-class knife will not cut well for long if it isn't properly cared for and maintained. Putting in the effort to learn correct sharpening technique, on the other hand, will not only keep your knife sharp but extend its lifespan and deepen your connection with it - just one of the small but profound ways a handcrafted knife can add something to one's life.

Fortunately, Musashi's staff are more than happy to demonstrate the skills you'll need and can even make sure you have the right tools to match your knife. Arming himself with a hefty blade featuring some pretty cherry blossom patterning, Clement began sliding it against a fine-grained whetstone with smooth, well-practised ease.

While sharpening in the west tends to be done with alternating forward and backward strokes, in Japan - where knives are more likely to be single-beveled - pushing the knife edge-forward is the more common motion. Key to the whole operation is maintaining a steady angle, typically just 10-15 degrees owing to the greater sharpness and slimmer bevels of Japanese knives. As Japanese steel tends to be harder but also more brittle, stropping is usually avoided in favor of finishing with a finer stone.

For one final highlight of my visit, I made my way upstairs and was amazed to find a full-sized and beautifully furnished bar known as YOKAI JAPAN with subtle details adding to the sense of authenticity and anchoring it in its Kyoto surroundings. Here, I was treated to "Emotion" - the more beginner-friendly of three sake tasting flights, nicely chosen to bring out the contrasts between dry and sweet, rich and clean.

A similar experience at Musashi's main Kappabashi Store in Tokyo last year had also been something I really enjoyed, so it was great to see the company building on this with something even more polished and engaging. Apart from the gorgeous setting and nice glassware, what really stood out here was my bartender for the experience - articulate, charming and effortlessly knowledgeable, she was in short just the right sort of person to guide someone through their first taste of sake.

Emotiontasting set

With that, it was time to say my goodbyes and begin my journey back to Tokyo. A year on from my first visit, MUSASHI JAPAN has made a strong enough impression that it remains one of just a handful of shops that I actively recommend to visiting friends, and even if I haven't yet bought the knife of my dreams, still I know exactly what it is (hint: it's a yanagiba) and where I'm going to get it from.

Other MUSASHI JAPAN stores in the Kansai area

MUSASHI JAPAN Kyoto Sanjo

604-8036 Kyoto, Nakagyo Ward, Ishibashicho, BiG BoSS

MUSASHI JAPAN Kyoto Kawaramachi

600-8001 Kyoto, Shimogyo Ward, Shido-dori, Kobashi Nishiiru Shinmachi 58 Ikezen, Minamigawa Building 1F

MUSASHI JAPAN Kyoto Shijo

600-8003 Kyoto, Shimogyo Ward, Otabimiyamotocho, 13 Sarasa Kayukoji

MUSASHI JAPAN Kyoto Kiyomizu

605-0862 Kyoto, Higashiyama Ward, Kiyomizu, 3 Chome-340

MUSASHI JAPAN Nara

630-8236 Nara, 14-1 Shimosanjocho 1F