A visit to the Setouchi Triennale

One of Japan's most celebrated art festivals, the Setouchi Triennale has been drawing visitors from around the world since its launch in 2010. Held once every three years across a network of islands in the Seto Inland Sea, the event was originally created to help revitalize a region struggling with depopulation and the lingering effects of industrial pollution. This year's edition features 254 works by 216 artists and introduces three new venues, including the recently opened Naoshima New Museum of Art, while the theme for 2025, "Restoring the Sea," reflects the festival's continued focus on environmental and community renewal.

As a lifelong fan of contemporary art, I'd been hoping to visit for some time, and finally got the opportunity to experience the Triennale firsthand this year. Over the course of two packed days, I explored three of the festival's main islands - each with its own unique atmosphere and creative highlights.

Taking inspiration from the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in Niigata as well as the Setouchi Region's own long standing ties to creative figures like Isamu Noguchi, Inokuma Genichiro and Tange Kenzo, the first triennale took place back in 2010, timed to coincide with the opening of several key museums and galleries. Ultimately, the Triennale was able to draw on a broad coalition of backers, with Kagawa Prefecture and Benesse - an Okayama-based publishing company and the owner of a collection of galleries on Naoshima - as its biggest contributors.

Over the following 15 years, the event has continued to grow from seven sites to a total of 12 islands and two major ports, also increasing in duration from a few weeks in summer to 107 days, divided into three separate seasons in spring, summer and autumn. Visitor numbers meanwhile increased steadily to 1.17 million in 2019, making it the largest festival of its kind in all of Asia.

Planning your visit

Spread across a large area and requiring multiple connections to get around, the Triennale can be a somewhat daunting destination to plan for, but also brings with it the chance to explore a unique and less-visited side of the Japanese landscape. For most visitors, the first task will be getting to grips with the network of local ferries connecting each of the islands.

This is actually very straightforward, especially for visitors based in the main hub port of Takamatsu - although visitors should note that ferry tickets are sold at the terminal on first-come-first-served basis. On busy days, some ferries fill up so you many not be able to ride your first choice of departure.

Our own information page provides a general introduction to the main islands and venues, while the official website and app offer more specific details like recommended itineraries, route guidance and real time updates for things like closures, congestion or weather related emergencies, while the official website is useful for looking up individual artworks, opening hours and timetables for buses and ferries.

Priced at 4,500 for a single season or 5,500 for the whole year, the Setouchi Triennale Passport includes one-time entry to most paid art facilities within the featured locations and offers good overall value for money, especially for returning or multi-day visitors. It's worth noting however that a small number of high profile sites like the Chichu Museum and Teshima Art Museum are not included and require separate tickets.

As the festival period can be extremely busy, I chose to visit outside the official dates to get a sense of how things would be affected. Despite a few disappointments - many attractions are closed, particularly indoor ones on the smaller islands - this way will still be preferable for some visitors looking for a quieter time.

Last but certainly not least, the transport available on each island can vary quite a bit, with buses or a rent-a-car recommended for larger islands like Shodoshima, while others like Ogijima can be comfortably explored on foot. Attractions on Naoshima meanwhile are grouped into multiple clusters that can be easily explored individually, but visitors will still need to walk for 30-60 minutes or take a bus or a rent-a-cycle to get between them.

Naoshima

The heart of the Setouchi Triennale and the first island on my list was Naoshima, located in the northern part of Kagawa Prefecture with an area of just eight square meters and a population of about 2,900. Despite its growing popularity as a tourist destination, the island's economic core remains its copper smelting industry, which was established by Mitsubishi in 1917 and still employs 60-70% of the people on the island. The facilities are located close to the island's northern tip and go unnoticed by many visitors, especially those arriving from the Takamatsu side.

Since its revival as an "art island", visitors have been drawn to Naoshima in large part by major galleries like Benesse House and the Chichu Museum - both part of the Benesse group and created by the legendary modern architect Ando Tadao. Among these, the latest is the Naoshima New Museum of Art, added in May of 2025.

Arriving into the island's northern port of Honmura from Uno by ferry, I stopped to pick up a rent-a-cycle from the nearby TVC Services branch and set off for Naoshima's southern coast, a downhill journey of just 6 minutes. Leaving the bike in a parking area, I passed through Benesse House's east gate and took a short walk along the beach to one of the island's more iconic sights - Kusama Yayoi's Pumpkin.

Placed here at the end of a pier in 1994, the work represented a major milestone in Kusama's career as her first permanent outdoor sculpture, said to represent the qualities of comfort, humility and regeneration. The current piece is actually a reinforced version of the original, which in 2021 was swept off the pier by a typhoon and badly damaged.

Just a short walk from the pier, I came to a nicely landscaped area with more free standing sculptures and several buildings attached to Benesse House - a beachside guesthouse and restaurant, gift shop and the main guest building, set a little further back from the seafront.

Designed like all the main buildings within the complex by Ando Tadao, the Benesse House Museum is a striking piece of brutalist design, with Ando's trademark exposed concrete creating a neutral, reflective space while more rustic stone elements on the exterior help to anchor it in Naoshima's island landscape.

Inside, a modest lobby leads into a narrow, curving corridor, itself wrapping around a tall, sunlit atrium that currently serves as a dramatic backdrop to the conceptual piece "100 Live and Die" by Bruce Nauman. Beyond, visitors are drawn into a long, split level gallery with several larger pieces and windows looking into enclosed courtyards or out over the surrounding hills.

As a longtime modern art lover, I found a lot to like about the building itself but was left just a little underwhelmed by some of the works themselves, the overall vibe feeling long on concept but a little lacking in spectacle and execution.

Leaving the museum behind, I retraced my steps back towards Honmura, turning inland just short of the harbor for my second stop of the day at the Naoshima New Museum of Art. Also designed by Ando Tadao and a part of the Benesse Group, the building shares a lot of features with its older counterparts, from expansive raw concrete surfaces to another central atrium with light streaming in from overhead. Connecting the museum's ground floor and two basement levels via a long, narrow staircase, the atrium leads into four attractive and well-lit gallery rooms, currently hosting the inaugural exhibition, entitled "From the Origin to the Future".

Here I found some striking stand-alone works by Ciai Guo Qiang, Murakami Takashi and others, but the most satisfying for me was a site-specific collection of works by ChimPom, Martha Atienza and Heri Dono, all located in the upper floor level and which came together with the feeling of walking through some magical, post-apocalyptic landscape.

Another spot within the museum well worth checking out is its cafe, another concrete and glass wonder with a spectacular eastward view across the water towards the neighboring island of Teshima. Here I enjoyed a beautifully prepared salad with a pot of hot, floral-scented green tea before continuing on my way to Honmura.

Extending out from the little harbor into a series of narrow backstreets, the Honmura area maintains the atmosphere of an old, rural townscape with a mix of historic houses, modest local businesses and a few small restaurants and cafes mixed in here and there. It's in this part of the island that the Art House Project - restoring and repurposing multiple abandoned homes, businesses and sacred spaces as artworks - began, something that has become a core tradition of the Triennale despite predating it by more than a decade.

Armed with a combination ticket for five of the "art houses", I made stops at Haisha (a former dentist's office), the Go'o Shrine and three former local residences, each with its own unique transformation. Despite some uneven results, I enjoyed the "treasure hunt" aspect of combing through the old town in search of surprising little spaces.

With the sky beginning to dark, I got back on my rent-a-cycle for the last leg across to the island's opposite coast and the main port of Miyanoura - here, I dropped off the bike and took in a final couple of artworks by the shore while I waited for my ferry to arrive.

Megijima

I began my second day at the Triennale by riding the first ferry out from Takamatsu Port to the little island of Megijima, a 20-minute crossing through gloomy weather with much of the landscape blanketed in a thick fog.

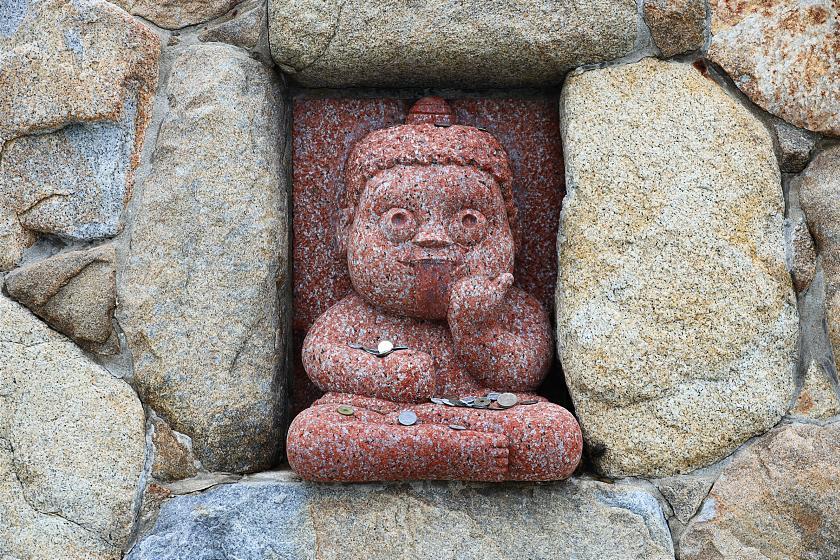

Covering only about 2.6 square kilometers, the island is best known today for its connection with the Momotaro or "Peach Boy" legend, in which a little boy is born from a giant peach and later embarks on an adventure to defeat a band of marauding ogres. Its name, meaning "female tree island", pairs with that of neighboring Ogijima, or "male tree island", suggesting a link with ancient Shinto lore, and while documentary sources are very limited up the Edo Period (1603-1868), what little we do know suggests a rich history with evidence of at least seasonal habitation going all the way back to the Jomon Period (13,000-300 BC).

Arriving into the harbor, I immediately noticed two eye-catching works along the sea front - a full-sized mock piano with four sail masts sprouting from its upper lid, titled 20th Century Recall, and Sea Gulls Parking Lot, about 300 two-dimensional seagulls arranged in rows along the sea wall and storm surge barriers. Equally impressive however are the long stone walls known as ote lining the opposite side of the street, guarding against the powerful winds that rock the island every winter.

Just a few steps from the water's edge, I made another brief stop at the Oninokan or "ogre's hall", a mix of souvenir store, tourist information center and bike rental shop. Despite being only a fraction of Naoshima's size, the island is still just a little too big to explore comfortably on foot, so jumping on my own rent-a-cycle I set off through the little town towards the next artwork on my list.

Set on what was once a series of rice terraces now left fallow in the foothills overlooking the harbor, Terrace Winds comprises some 400 ceramic pieces, stacked in rows to resemble skeletonised archaeological remains with the surrounding grass and scrub already rising up to swallow it. Even with the view spoiled a little by the fog, it felt like an impactful statement on the island's vanished agricultural tradition and left me wondering how the same scene would look in another decade or two.

Leaving the artwork behind, I continued to wind my way up the island's steep central hill, called Washigamine, or Eagle's Peak. It was here that a medium-sized cave system was discovered which, although more likely an old mine or storehouse, soon became linked with the Momotaro story as the "ogre's secret base".

While the cave itself offers little to write home about, the atmosphere is somewhat enhanced by piles of onigawara roof tiles - a kind of ceramic capstone with the head of an ogre, typically placed at the gable ends or ridge lines of some traditional buildings. Visitors can also see several cave murals added as part of the Setouichi Triennale.

By now it was approaching mid-day, so I retraced my steps towards the harbor where I dropped off my rental bike and found a comfy spot to await the next ferry. Overall, I had certainly enjoyed my first time on the island but with so many of its attractions closed out of season, it is one that I would recommend visiting during the official Triennale dates.

Ogijima

The final stop of my visit was at Ogijima, located just slightly to the north. Smaller even than Megijima, the island was best known until the 1950s for raising cattle, which would be rented out to other communities across the water in exchange for rice - the steep slopes of Ogijima itself offering little space for crops of their own. Since then, the population has steadily decreased and today fewer than 150 residents call it their permanent home.

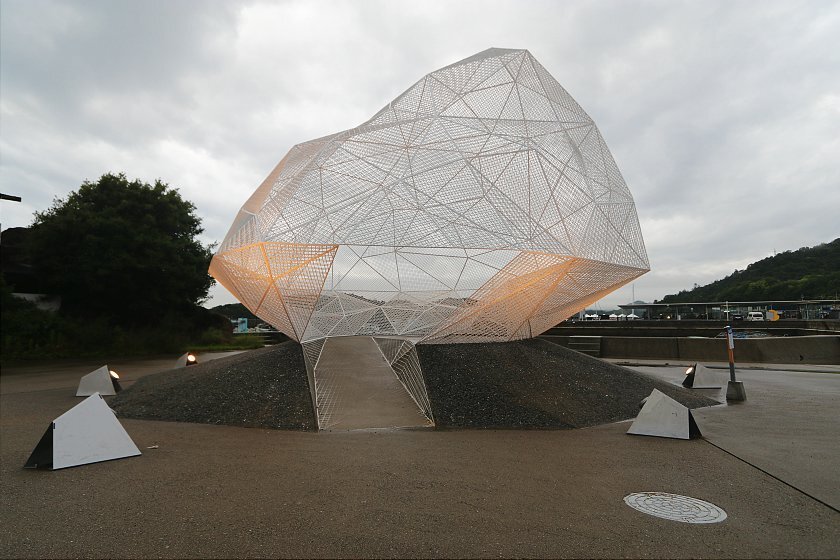

By now the weather was beginning to brighten, and my first look at the island's only village as we approached the harbor proved one of the most memorable moments of the entire trip. Stepping off the ferry, I began with a look at the two nearest artworks - Ogijima's Soul is a sleek, modern pavilion that doubles as an information center and ticket booth, while Takotsuboru is a small children's play area recalling the island's tradition of octopus fishing.

The highlight of the island for me was exploring the village - a maze of narrow streets and charming wooden houses, some decorated with vertical strips of scrap construction material by artist Manabe Rikuji to create lively, semi-abstract murals.

With so many little houses crammed together on the steep hillside, I appreciated that artworks, cafes and restaurants were well signposted, with clear warnings letting you know when to go no further.

Close to the upper limit of the village area, found the Ogijima Pavilion - a modest but fascinating structure by the architect Ban Shigeru largely out of sustainable cardboard tubes. Sadly, with the interior closed outside of festival dates I was limited to admiring the outside.

With the village area covered, took a path cutting across the interior to the island's south coast, passing a little fishing port before eventually arriving at Walking Ark. Created by Yamaguchi Keisuke in response to the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami, this striking work takes the form of a mountain range marching into the distance on four pairs of legs. According to the artist himself, who often uses arks of various kinds together with imagery representing hope or escape, the meaning is something akin to a prayer for protection from man-made or environmental crises.

Still with a little time on my hands before my next ride back to the mainland, I set out for a stroll along the island's west coast, soon arriving at its northern tip. Here, I found the Ogijima Lighthouse, an elegant granite structure dating to 1895, today ranked as one of Japan's 50 best lighthouses. Pausing for a rest on a nearby stretch of sandy beach, I watched a series of cargo freighters pass languidly by until it was time to hurry back to the town and my waiting ferry.

Just like my time on Megijima that morning, my experience on Ogijima was definitely somewhat curtailed by visiting outside of the Triennale dates, but somewhere between the charm of the village area and its locals, the beautiful views out to sea and the slightly better selection of artworks to enjoy I was left feeling much more satisfied, and more motivated than ever to see more of this endlessly fascinating part of the country.