Tea

Tea is the most popular beverage in Japan and an important part of Japanese food culture. Various types of tea are widely available and consumed at any point of the day. Green tea is the most common type of tea, and when someone mentions "tea" (é©Æā, ocha) without specifying the type, it is green tea to which is referred. Green tea is also the central element of the tea ceremony. Among the most famous places for tea cultivation are Shizuoka, Kagoshima and Uji.

The following is a list of the main varieties of tea that are popularly consumed in Japan:

Tea from tea plant

Tea not from tea plant

Where tea can be found

Tea of one kind or another, hot or cold, can be found practically at all restaurants, vending machines, kiosks, convenience stores and supermarkets.

At restaurants, green tea is often served with or at the end of a meal for free. At lower end restaurants, green tea or mugicha tend to be available free for self-service, while konacha is commonly provided at inexpensive sushi restaurants. Kocha (black tea) is usually available alongside coffee at cafes and Western restaurants.

At some temples and gardens, tea (usually ryokucha or matcha) is served to tourists. The tea is typically served in a tranquil tatami room with views onto beautiful scenery, often together with an accompanying Japanese sweet. While the tea is sometimes included in the temple's or garden's admission fee, it more often requires a separate fee of a few hundred yen.

Last but not least, many types of tea are sold in PET bottles and cans at stores and vending machines across Japan. They are available both hot or cold, although hot tea is less widely available during the summer months, especially at vending machines.

Japanese tea and a brief history

Tea was introduced to Japan from China in the 700s. During the Nara Period (710-794), tea was a luxury product only available in small amounts to priests and noblemen as a medicinal drink.

Around the beginning of the Kamakura Period (1192-1333), Eisai, the founder of Japanese Zen Buddhism, brought back from China the custom of making tea from powdered leaves. Subsequently, the cultivation of tea spread across Japan, notably at Kozanji Temple in Takao and in Uji.

During the Muromachi Period (1333-1573), tea gained popularity among people of all social classes. People gathered in big tea drinking parties and played a guessing game, whereby participants, after drinking from cups of tea, guessed the names of tea and where they came from. Collecting and showing off prized tea utensils was also popular among the affluent.

At about the same time, a more refined version of tea parties developed with Zen-inspired simplicity and a greater emphasis on etiquette and spirituality. These gatherings were attended by only a few people in a small room where the host served the guests tea, allowing greater intimacy. It is from these gatherings that the tea ceremony has its origins.

Questions? Ask in our forum.

Restaurants

-

-

![]() Udatsu Sushi (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2024 - People from around the world visit to experience Mr. Udatsu's sushi. Inside the restaurant, which resembles an art gallery with its modern decor and numerous artworks, guests can enjoy sushi crafted from the highest quality ingredients. While the foundation is traditional nigiri, the menu also features original creations born from the chef's relentless curiosity and innovation.View on JapanEatinerary

Udatsu Sushi (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2024 - People from around the world visit to experience Mr. Udatsu's sushi. Inside the restaurant, which resembles an art gallery with its modern decor and numerous artworks, guests can enjoy sushi crafted from the highest quality ingredients. While the foundation is traditional nigiri, the menu also features original creations born from the chef's relentless curiosity and innovation.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Waketokuyama (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2025 - With a meticulous focus on allowing guests to enjoy seasonal ingredients at their peak, the menu changes approximately every two weeks. The signature dish, "Grilled Abalone with Seaweed Aroma," features thick slices of abalone generously coated in a rich liver sauce, offering an exquisite taste of the sea.View on JapanEatinerary

Waketokuyama (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2025 - With a meticulous focus on allowing guests to enjoy seasonal ingredients at their peak, the menu changes approximately every two weeks. The signature dish, "Grilled Abalone with Seaweed Aroma," features thick slices of abalone generously coated in a rich liver sauce, offering an exquisite taste of the sea.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Sushiroku (Osaka)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A cozy, family-run restaurant managed by a husband and wife. They are deeply committed to perfecting their shari (sushi rice) and use two types of vinegared rice tailored to complement each topping. Since 2019, the restaurant has consistently earned stars.View on JapanEatinerary

Sushiroku (Osaka)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A cozy, family-run restaurant managed by a husband and wife. They are deeply committed to perfecting their shari (sushi rice) and use two types of vinegared rice tailored to complement each topping. Since 2019, the restaurant has consistently earned stars.View on JapanEatinerary -

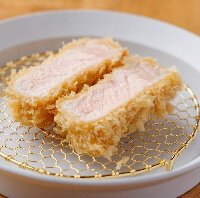

![]() Fry-ya (Tokyo)Exquisite fried dishes crafted by a head chef with experience earning stars in both Switzerland and Japan. The remarkably light tonkatsu is a favorite not only among Japanese diners but also among visitors to Japan. With the theme of "small portions, many varieties," guests can enjoy sampling a wide selection of tonkatsu in smaller portions.View on JapanEatinerary

Fry-ya (Tokyo)Exquisite fried dishes crafted by a head chef with experience earning stars in both Switzerland and Japan. The remarkably light tonkatsu is a favorite not only among Japanese diners but also among visitors to Japan. With the theme of "small portions, many varieties," guests can enjoy sampling a wide selection of tonkatsu in smaller portions.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Sushi Hayashi (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A unique sushi restaurant that blends traditional Edomae (Tokyo-style) sushi with Kyoto-style sushi, such as mackerel sushi and steamed sushi, in its courses. The head chef, who trained as a sushi artisan in Switzerland, carefully selects Swiss wines, making them a perfect pairing to enjoy with the meal.View on JapanEatinerary

Sushi Hayashi (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A unique sushi restaurant that blends traditional Edomae (Tokyo-style) sushi with Kyoto-style sushi, such as mackerel sushi and steamed sushi, in its courses. The head chef, who trained as a sushi artisan in Switzerland, carefully selects Swiss wines, making them a perfect pairing to enjoy with the meal.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Hikarimono (Tokyo)With a prime location and quality that rivals high-end sushi restaurants, this restaurant maintains the goal of being a place for everyday dining. It offers a casual and relaxed atmosphere, free from stiffness or formality. The signature "Hikari-maki," featuring ingredients such as sardines, pickled plum, and bettarazuke (sweet pickled radish), boasts unique flavors that are especially popular among international visitors.View on JapanEatinerary

Hikarimono (Tokyo)With a prime location and quality that rivals high-end sushi restaurants, this restaurant maintains the goal of being a place for everyday dining. It offers a casual and relaxed atmosphere, free from stiffness or formality. The signature "Hikari-maki," featuring ingredients such as sardines, pickled plum, and bettarazuke (sweet pickled radish), boasts unique flavors that are especially popular among international visitors.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Noguchi Tsunagu (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - The sister restaurant of the highly exclusive Japanese cuisine establishment, Kyotenjin Noguchi. While maintaining the culinary essence of the main branch, this kappo-style restaurant incorporates ingredients from the chefŌĆÖs hometown in the Goto Islands. Its signature dish, Nikusui, is a masterpiece made from carefully prepared, top-quality A5-grade sirloin.View on JapanEatinerary

Noguchi Tsunagu (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - The sister restaurant of the highly exclusive Japanese cuisine establishment, Kyotenjin Noguchi. While maintaining the culinary essence of the main branch, this kappo-style restaurant incorporates ingredients from the chefŌĆÖs hometown in the Goto Islands. Its signature dish, Nikusui, is a masterpiece made from carefully prepared, top-quality A5-grade sirloin.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() TEMPURA & WINE SHINO (Tokyo)The kind of restaurant that is known only to true gourmets, serving as a sort of 'Hidden gem'. In a chic space with black walls and a ceiling adorned in gold, you can enjoy tempura with a light and elegant texture, delicately fried using refined techniques to achieve a thin, white batter that minimizes the aroma of oil. Savor tempura that maximizes the flavors of the ingredients, paired with Champagne and Burgundy wines carefully selected by the sommelier.View on JapanEatinerary

TEMPURA & WINE SHINO (Tokyo)The kind of restaurant that is known only to true gourmets, serving as a sort of 'Hidden gem'. In a chic space with black walls and a ceiling adorned in gold, you can enjoy tempura with a light and elegant texture, delicately fried using refined techniques to achieve a thin, white batter that minimizes the aroma of oil. Savor tempura that maximizes the flavors of the ingredients, paired with Champagne and Burgundy wines carefully selected by the sommelier.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Ginza Nominokoji Yamagishi (Tokyo)Tominokoji Yamagishi, an exclusive kaiseki restaurant from Kyoto, has opened its first location in Tokyo. Unlike its main branch, this establishment adopts an izakaya-style format, allowing diners to enjoy a more relaxed ├Ā la carte dining experience. Despite being located in Tokyo, the restaurant meticulously sources ingredients and even water from Kyoto, dedicating itself to faithfully recreating KyotoŌĆÖs culinary traditions.View on JapanEatinerary

Ginza Nominokoji Yamagishi (Tokyo)Tominokoji Yamagishi, an exclusive kaiseki restaurant from Kyoto, has opened its first location in Tokyo. Unlike its main branch, this establishment adopts an izakaya-style format, allowing diners to enjoy a more relaxed ├Ā la carte dining experience. Despite being located in Tokyo, the restaurant meticulously sources ingredients and even water from Kyoto, dedicating itself to faithfully recreating KyotoŌĆÖs culinary traditions.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Kitashinchi Kushikatsu Bon (Osaka)A restaurant that elevates Osaka's soul food, kushikatsu, to a luxurious level. Skilled chefs meticulously prepare each skewer using carefully selected premium ingredients such as Chateaubriand and foie gras. The skewers are fried in a custom copper pot using a unique oil blend based on cottonseed oil, enhancing the natural flavors of the ingredients.View on JapanEatinerary

Kitashinchi Kushikatsu Bon (Osaka)A restaurant that elevates Osaka's soul food, kushikatsu, to a luxurious level. Skilled chefs meticulously prepare each skewer using carefully selected premium ingredients such as Chateaubriand and foie gras. The skewers are fried in a custom copper pot using a unique oil blend based on cottonseed oil, enhancing the natural flavors of the ingredients.View on JapanEatinerary

-