Sake

Sake is an alcoholic drink made from fermented rice. Often referred to as nihonshu (ú{ð) in Japanese (to differentiate it from "sake" which in Japanese can also refer to alcohol in general), the drink enjoys widespread popularity and is served at all types of restaurants and drinking establishments. And as interest in Japanese cuisine has grown internationally, sake has started to become a trendy and recognizable drink around the world.

The foundations of good sake are quality rice, clean water, koji mold and yeast. They are combined and fermented in precise processes that have been refined over the centuries. Typically filtered (although unfiltered products are also available), the resulting clear to slightly yellowish rice wines have an alcohol content of around 15 percent and relatively mild flavor profiles, ranging from light and crisp to richer, more substantial, fruity notes. Sake pairs well with almost any kind of food but compliments the delicate flavors of traditional Japanese meals particularly well.

Types of sake

In recent decades, premium sake has been gaining popularity, while cheap sake has gradually lost market share to other types of alcoholic drinks. Premium sake differentiates itself in the quality of the ingredients and the efforts put into the production process. Below are some of the factors that make a difference and the terms that help consumers understanding them:

Degree of polishing the rice

Rice grains are polished before used in the sake production because the grains' outer layers create undesirable flavors in the end product. Generally speaking, the more polished the rice is, the better gets the taste and the higher gets the price tag of the resulting sake. For premium sake, at least 30 percent of the grain has usually been polished away, while the rice for the following high-end types of sake need to be polished even more:

- Ginjo (áø) - at least 40 percent of the grain has been polished away.

- Daiginjo (åáø) - at least 50 percent of the grain has been polished away.

Generally speaking, ginjo and daiginjo tend to be the most flavorful types of premium sake and rich in character. As a result, they are best enjoyed by themselves (e.g. as aperitif) or together with strongly flavored dishes. They can be too powerful when paired with delicate dishes.

Addition of alcohol

The alcohol in sake is produced in a time and cost consuming fermentation process. In order to decrease production costs, many producers have been adding large amounts of distilled alcohol to their sake. Premium sake, however, pride themselves for not containing any added alcohol or for using only small amounts of it with the purpose of adding subtle flavors. This leads to the following additional classifications of premium sake:

- Junmai (Ä) - no alcohol has been added to the sake.

- Honjozo ({ø¢) - a small amount of alcohol has been added to enhance the flavor.

Some of the above terms can be combined. For example, a "Junmai Ginjo" sake is not using any added alcohol and is made of rice grains that have been polished by at least 40 percent.

Special types of sake

By omitting or adding certain steps to the sake production process, some special types of sake can be produced. Below are some of the more common types encountered:

- Namazake (raw sake)

Most sake is pasteurized towards the end of the production process. However, in case of namazake, the pasteurization step is skipped. The resulting drink has a fresh flavor and must be refrigerated and consumed quickly. - Nigorizake (cloudy sake)

Most sake is filtered towards the end of the production process to produce a perfectly clear drink. Nigorizake, however, is only coarsely filtered, resulting in a cloudy sake that contains some of the rice solids left over from fermentation. The taste of nigorizake ranges from very sweet to tart. - Sparkling sake

In recent years, more and more sake brewers have added a sparkling sake to their product line-up. Similar to sparkling wine, sparkling sake is bottled before the fermentation process has fully ended, resulting in the creation of bubbles. - Koshu (old sake)

Most sake is usually drunk within a few months of production. However, there is a class of sake, called koshu, that has been aged in bottles or barrels for longer periods to develop new flavor profiles. Depending on how the sake was aged, the resulting koshu often has stronger, earthy or woody tones and a darker, honeyed color. - Jizake (local sake)

Jizake is sake that is produced locally by small, independent brewers. - Amazake (sweet sake)

Although not true sake, amazake is a sweet, thickened, low or non alcoholic drink that is typically served during the cold winter months. You will often find amazake being sold at food stands and street vendors around winter festivals.

How to enjoy sake

Sake can be found at most establishments serving alcohol, especially at restaurants and drinking establishments such as izakaya and bars. There are also specialty sake bars that stock a wide range of sake from various regions.

Similar to wine, sake comes in a range of flavors that vary in complexity and nuance. At the most basic level, sake is described as either sweet (ama-kuchi) or dry (kara-kuchi). The sweetness of sake is often listed on the menu with a number value known as the sake meter value (nihonshudo). The scale goes from -15 (very sweet) to +15 (very dry).

Sake is also served at a variety of temperatures depending on the sake, season and individual taste. Generally speaking, most premium sake is best enjoyed chilled or at room temperature (especially the expensive ginjo and daiginjo), while cheaper and less flavorful sake holds up well when served hot (called atsukan) and can be very enjoyable especially during the cold winter months. When in doubt, consult the server for a recommendation.

At restaurants, the amount of sake is commonly sold in the traditional unit called go () which corresponds to about 180 ml, e.g. ichi-go (one go), ni-go (two go), etc. In addition, small bottles (300 ml) and larger bottles (720 ml) are often available. Sake is commonly served in small sake cups, a glass or a glass placed into a wooden box (masu).

When drinking in groups, it is customary to serve one another rather than just serving yourself. You should periodically check your friends' glasses and replenish them before they get empty. Likewise, if someone serves you, you should hold up your glass towards the person and then take one sip before putting the glass down.

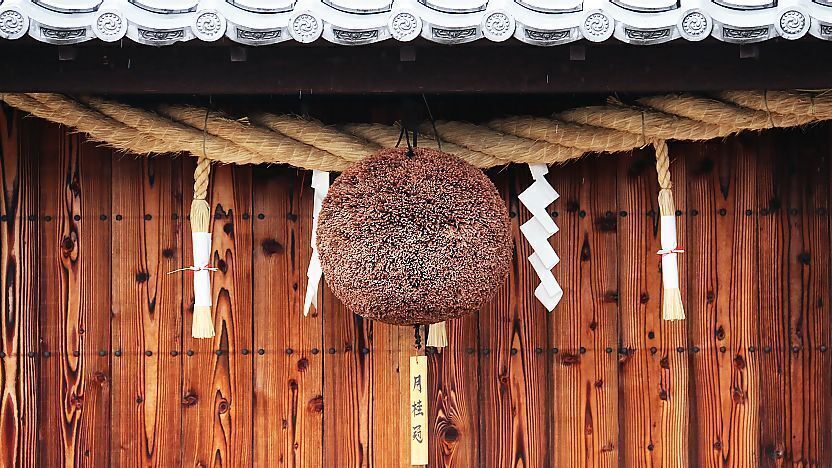

Visiting a brewery

There are currently about 1800 sake breweries across Japan, especially in the famous sake producing regions such as Niigata, Kobe and Kyoto. Some of the breweries offer tours of their facilities, although these are often in Japanese only and may require advance reservations.

Note that sake production is seasonal with most of the action taking place in winter. Access to the breweries may be restricted during the busy sake making months, and in turn, there may not be a lot to see during the off-season. Some breweries also maintain a museum or an on-site shop where their products are on sale. Sampling of the sake may also be possible at some of these shops.

Some sake-related attractions

Questions? Ask in our forum.

Restaurants

-

-

![]() Udatsu Sushi (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2024 - People from around the world visit to experience Mr. Udatsu's sushi. Inside the restaurant, which resembles an art gallery with its modern decor and numerous artworks, guests can enjoy sushi crafted from the highest quality ingredients. While the foundation is traditional nigiri, the menu also features original creations born from the chef's relentless curiosity and innovation.View on JapanEatinerary

Udatsu Sushi (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2024 - People from around the world visit to experience Mr. Udatsu's sushi. Inside the restaurant, which resembles an art gallery with its modern decor and numerous artworks, guests can enjoy sushi crafted from the highest quality ingredients. While the foundation is traditional nigiri, the menu also features original creations born from the chef's relentless curiosity and innovation.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Waketokuyama (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2025 - With a meticulous focus on allowing guests to enjoy seasonal ingredients at their peak, the menu changes approximately every two weeks. The signature dish, "Grilled Abalone with Seaweed Aroma," features thick slices of abalone generously coated in a rich liver sauce, offering an exquisite taste of the sea.View on JapanEatinerary

Waketokuyama (Tokyo)Awarded One Star in 2025 - With a meticulous focus on allowing guests to enjoy seasonal ingredients at their peak, the menu changes approximately every two weeks. The signature dish, "Grilled Abalone with Seaweed Aroma," features thick slices of abalone generously coated in a rich liver sauce, offering an exquisite taste of the sea.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Sushiroku (Osaka)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A cozy, family-run restaurant managed by a husband and wife. They are deeply committed to perfecting their shari (sushi rice) and use two types of vinegared rice tailored to complement each topping. Since 2019, the restaurant has consistently earned stars.View on JapanEatinerary

Sushiroku (Osaka)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A cozy, family-run restaurant managed by a husband and wife. They are deeply committed to perfecting their shari (sushi rice) and use two types of vinegared rice tailored to complement each topping. Since 2019, the restaurant has consistently earned stars.View on JapanEatinerary -

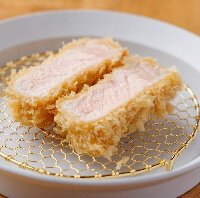

![]() Fry-ya (Tokyo)Exquisite fried dishes crafted by a head chef with experience earning stars in both Switzerland and Japan. The remarkably light tonkatsu is a favorite not only among Japanese diners but also among visitors to Japan. With the theme of "small portions, many varieties," guests can enjoy sampling a wide selection of tonkatsu in smaller portions.View on JapanEatinerary

Fry-ya (Tokyo)Exquisite fried dishes crafted by a head chef with experience earning stars in both Switzerland and Japan. The remarkably light tonkatsu is a favorite not only among Japanese diners but also among visitors to Japan. With the theme of "small portions, many varieties," guests can enjoy sampling a wide selection of tonkatsu in smaller portions.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Sushi Hayashi (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A unique sushi restaurant that blends traditional Edomae (Tokyo-style) sushi with Kyoto-style sushi, such as mackerel sushi and steamed sushi, in its courses. The head chef, who trained as a sushi artisan in Switzerland, carefully selects Swiss wines, making them a perfect pairing to enjoy with the meal.View on JapanEatinerary

Sushi Hayashi (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - A unique sushi restaurant that blends traditional Edomae (Tokyo-style) sushi with Kyoto-style sushi, such as mackerel sushi and steamed sushi, in its courses. The head chef, who trained as a sushi artisan in Switzerland, carefully selects Swiss wines, making them a perfect pairing to enjoy with the meal.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Hikarimono (Tokyo)With a prime location and quality that rivals high-end sushi restaurants, this restaurant maintains the goal of being a place for everyday dining. It offers a casual and relaxed atmosphere, free from stiffness or formality. The signature "Hikari-maki," featuring ingredients such as sardines, pickled plum, and bettarazuke (sweet pickled radish), boasts unique flavors that are especially popular among international visitors.View on JapanEatinerary

Hikarimono (Tokyo)With a prime location and quality that rivals high-end sushi restaurants, this restaurant maintains the goal of being a place for everyday dining. It offers a casual and relaxed atmosphere, free from stiffness or formality. The signature "Hikari-maki," featuring ingredients such as sardines, pickled plum, and bettarazuke (sweet pickled radish), boasts unique flavors that are especially popular among international visitors.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Noguchi Tsunagu (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - The sister restaurant of the highly exclusive Japanese cuisine establishment, Kyotenjin Noguchi. While maintaining the culinary essence of the main branch, this kappo-style restaurant incorporates ingredients from the chefâs hometown in the Goto Islands. Its signature dish, Nikusui, is a masterpiece made from carefully prepared, top-quality A5-grade sirloin.View on JapanEatinerary

Noguchi Tsunagu (Kyoto)Awarded One Star in 2024 - The sister restaurant of the highly exclusive Japanese cuisine establishment, Kyotenjin Noguchi. While maintaining the culinary essence of the main branch, this kappo-style restaurant incorporates ingredients from the chefâs hometown in the Goto Islands. Its signature dish, Nikusui, is a masterpiece made from carefully prepared, top-quality A5-grade sirloin.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() TEMPURA & WINE SHINO (Tokyo)The kind of restaurant that is known only to true gourmets, serving as a sort of 'Hidden gem'. In a chic space with black walls and a ceiling adorned in gold, you can enjoy tempura with a light and elegant texture, delicately fried using refined techniques to achieve a thin, white batter that minimizes the aroma of oil. Savor tempura that maximizes the flavors of the ingredients, paired with Champagne and Burgundy wines carefully selected by the sommelier.View on JapanEatinerary

TEMPURA & WINE SHINO (Tokyo)The kind of restaurant that is known only to true gourmets, serving as a sort of 'Hidden gem'. In a chic space with black walls and a ceiling adorned in gold, you can enjoy tempura with a light and elegant texture, delicately fried using refined techniques to achieve a thin, white batter that minimizes the aroma of oil. Savor tempura that maximizes the flavors of the ingredients, paired with Champagne and Burgundy wines carefully selected by the sommelier.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Ginza Nominokoji Yamagishi (Tokyo)Tominokoji Yamagishi, an exclusive kaiseki restaurant from Kyoto, has opened its first location in Tokyo. Unlike its main branch, this establishment adopts an izakaya-style format, allowing diners to enjoy a more relaxed à la carte dining experience. Despite being located in Tokyo, the restaurant meticulously sources ingredients and even water from Kyoto, dedicating itself to faithfully recreating Kyotoâs culinary traditions.View on JapanEatinerary

Ginza Nominokoji Yamagishi (Tokyo)Tominokoji Yamagishi, an exclusive kaiseki restaurant from Kyoto, has opened its first location in Tokyo. Unlike its main branch, this establishment adopts an izakaya-style format, allowing diners to enjoy a more relaxed à la carte dining experience. Despite being located in Tokyo, the restaurant meticulously sources ingredients and even water from Kyoto, dedicating itself to faithfully recreating Kyotoâs culinary traditions.View on JapanEatinerary -

![]() Kitashinchi Kushikatsu Bon (Osaka)A restaurant that elevates Osaka's soul food, kushikatsu, to a luxurious level. Skilled chefs meticulously prepare each skewer using carefully selected premium ingredients such as Chateaubriand and foie gras. The skewers are fried in a custom copper pot using a unique oil blend based on cottonseed oil, enhancing the natural flavors of the ingredients.View on JapanEatinerary

Kitashinchi Kushikatsu Bon (Osaka)A restaurant that elevates Osaka's soul food, kushikatsu, to a luxurious level. Skilled chefs meticulously prepare each skewer using carefully selected premium ingredients such as Chateaubriand and foie gras. The skewers are fried in a custom copper pot using a unique oil blend based on cottonseed oil, enhancing the natural flavors of the ingredients.View on JapanEatinerary

-

Experiences

-

-

![]() SponsoredTaste Traditional and Innovative Sake with a Terroir Tour of Nagai Sake Brewery in Kawaba Village, GunmaNagai Sake Brewery was founded in 1886 in Gunma Prefecturefs Kawaba Village, a locale brimming with natural beauty. In this experience, tour the breweryfs terroir – the natural environment whose distinctive features all factor into the flavor of its sake. Enjoy a toast at the source of the natural waters which are crucial to the sakefs brewing process, and a tour of the fields of rice from the townfs special brand of Yukinhotaka rice is grown. Finally, enjoy a tasting of three signature brands of Nagai sake at their special gSHINKAh tasting room.View experienceSponsored

SponsoredTaste Traditional and Innovative Sake with a Terroir Tour of Nagai Sake Brewery in Kawaba Village, GunmaNagai Sake Brewery was founded in 1886 in Gunma Prefecturefs Kawaba Village, a locale brimming with natural beauty. In this experience, tour the breweryfs terroir – the natural environment whose distinctive features all factor into the flavor of its sake. Enjoy a toast at the source of the natural waters which are crucial to the sakefs brewing process, and a tour of the fields of rice from the townfs special brand of Yukinhotaka rice is grown. Finally, enjoy a tasting of three signature brands of Nagai sake at their special gSHINKAh tasting room.View experienceSponsored

-