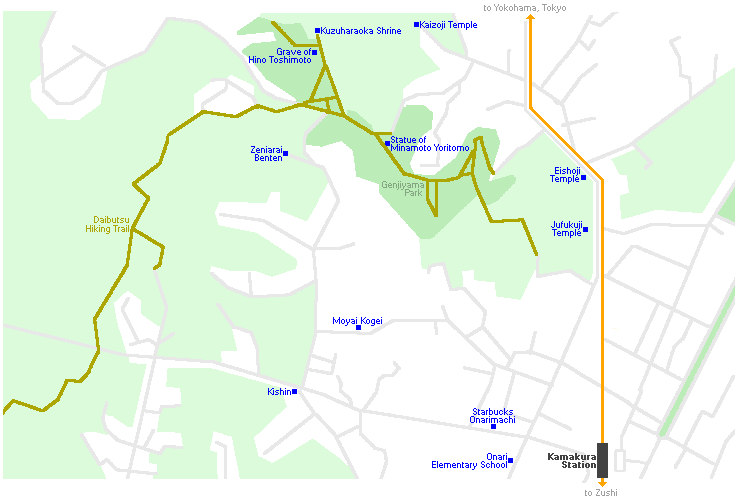

Kamakura Rediscovered - Onari

Following on from my previous piece exploring the area around the Komachi Dori shopping street, I soon find myself back in the historic city of Kamakura, this time taking in the west side of town in a single, wide loop. Although the weather forecast calls for rain later in the day, the sky is bright and clear as I arrive into the station.

Ifve often heard that Kamakura is especially beautiful in spring, and as I make my way from the stationfs west exit and along Onari Dori it is easy to understand why - every street seems alive with lush, dense greenery and flashes of color from azaleas and wisteria. Despite the picture-perfect surroundings however, there is little sign of the crowds I encountered on my last visit.

Located just a few steps off of Onari Dori is the site of a former imperial villa, now an elementary school. While little remains of the original structure, the school retains its impressive ironclad gate as well as the distinctive lines of its roof, sadly covered for renovation at the time of my visit.

Just across the road, a sleek, wedge-shaped Starbucks occupies a space that was once the studio of Yokoyama Ryuichi, an early and celebrated manga artist. Through large bay windows and a sheltered terrace, the stylish cafe overlooks a preserved section of the original garden, complete with a period swimming pool, cherry blossom tree and hanging wisterias.

Continuing uphill past the city hall and through a small tunnel, I stop for an early lunch at Kishin - a restaurant offering hearty, healthy traditional fare with a Zen-influenced aesthetic.

At the heart of the meal is rice cooked the old fashioned way - over a naked flame in a special clay pot called a donabe. This is also served in two parts, with a miniature al-dente portion followed by the rest after it has been allowed to steam, the better to appreciate the simple beauty of this all-important staple.

Complimenting the home-cooked quality of the cuisine, the atmosphere was light and relaxed, and I soon find myself chatting and laughing with the staff and other guests through our masks and plastic screens.

After finishing my meal and saying goodbye, I turn right off of Onari Dori and into a quiet residential street leading up to Zeniarai Benten Shrine.

On the way, I make a brief stop at Moyai Kogei, a craft store located in a charming period-style house. Hidden away behind a tiny garden overflowing with greenery, the shopfs interior is packed wall to wall with hundreds of delicate ceramic pieces from all over Japan, as well as some painted glass and intricately hand-woven baskets.

Further up the hill, I arrive at the entrance to Zeniarai Benten Shrine - a narrow tunnel in a leafy rock wall, marked by a carved stone tablet and torii gate.

Known both for its natural water springs and location within a tiny, hidden valley, the shrine is said to have been founded by the shogun Minamoto Yoritomo himself, following a vision of the snake-headed deity Ugafukujin. While there is little in the historical record to support this version of events, we do know that the springs were regarded as sacred since ancient times, and that the local custom of using it to wash money dates back to at least the 13th century.

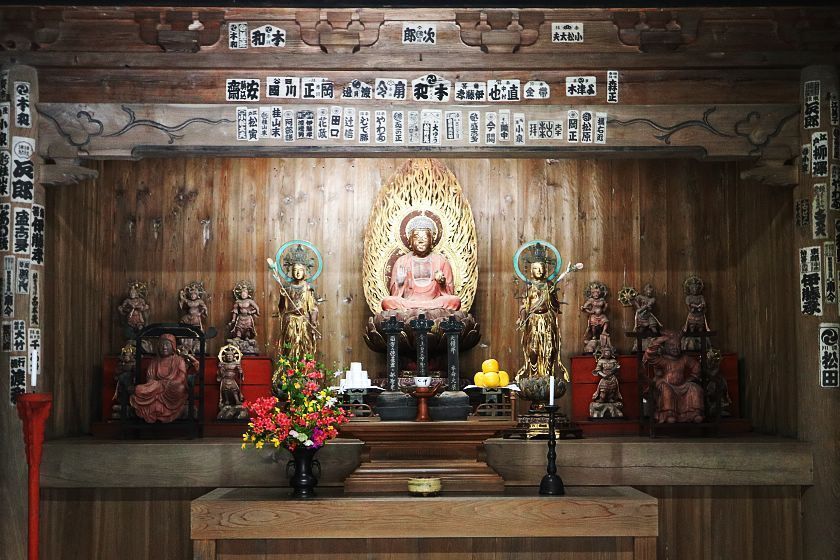

Entering the shrine precinct through the narrow tunnel, I am immediately struck by the many rows of torii, and the rich smell of incense - two things rarely found together. In fact, Zeniarai Benten is a rare surviving example of fusion between Shinto and Buddhism since the two religions were forcibly separated during the Meiji Period.

Before ritually purifying their money, visitors must each collect a candle, a bundle of incense and a small basket from a priest at the shrinefs main building. After lighting a candle at one of several altars, they can use the tiny flame to light the incense in turn and place this inside a large iron burner. Once this is done, they enter the Okugo - a cave where the sacred water flows. Here, they place coins, notes and even credit cards into their baskets before washing it in the sacred water.

Making my way out of the shine via the front entrance, I turn left and follow the road uphill past the entrance to the Daibutsu Hiking Trail and into Genjiyama Park, a pleasant grassy space taking its name from the alternate reading of the Minamoto name. Here, against a backdrop of trees, blossoms and flowering shrubs, I come face to face with Minamoto Yoritomo himself, seated in full armor on a plinth resembling a section of castle wall.

Turning east, I follow a path lined with thick undergrowth along the crest of the hill to Kuzuharaoka Jinja. Although relatively new, the shrine is dedicated to the spirit of Hino Toshimoto, a noble of the late Kamakura Period executed on this site after attempting to raise troops against the military government. His grave can be found in a shaded spot a few steps from the shrine entrance.

Today, the shrine is best known for its enmusubi-ishi or matchmaking stones, a popular power-spot for those seeking luck in love and marriage.

After exploring the shrinefs leafy precinct, I double back towards Genjiyama Park then descend a rocky and overgrown pathway to the north east, finally emerging in another quiet residential area.

At the end of a tree-lined street beside a gently murmuring stream, I arrive at the entrance to Kaizoji, a beautiful little temple of the Rinzai Buddhist school. Once the site of a much larger complex, destroyed by fire when the Kamakura Shogunate fell, the temple is today best known for its profusion of flowers, including crabapple, bellflower and hydrangeas.

By now my route has taken me almost full circle, but there is still time for one last quick stop as I again meet the train tracks and follow them south towards the station. A picturesque little temple of the Jodo school, Eishoji is Kamakurafs only nunnery and notable for surviving from its creation in the early Edo Period to the present with its original buildings intact.

The templefs founder - one Lady Okaji - was an interesting character about whom a number of stories are told. Born a minor aristocrat, she became the concubine of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu and gave birth to the last of his children, a girl who sadly died at a young age. She later became the adoptive mother of one of Ieyasufs sons, who would go on to become the ruler of Mito Province, in what is today Ibaraki Prefecture. Thereafter, generations of Mito princesses would become priestesses here, giving rise to its nickname "the palace of Mito".

With the sky beginning to darken, I make my way out of the temple and follow the train tracks south for ten minutes, arriving at the station just as the first raindrops begin to fall.