Echizen, the city of artisans and traditional crafts

Monozukuri is the art of making things, which embodies the soul of an artisan. The word is synonymous with traditional crafts and includes also the background and skills that go into producing them. Also incorporated into monozukuri is the spirit of upcycling and reusing items, in which the lifespan of an object is extended through repairs and repurposing.

Echizen, in Fukui Prefecture, is a monozukuri city that is known for its traditional crafts of forging blades, lacquerware, making wooden chests and washi paper. Located along the Sea of Japan, the city was also within a suitable distance from the former capital of Kyoto: neither too far nor too close. Thanks to its favorable geographical position and the availability of raw materials in the area, Echizen attracted many merchants and artisans during the feudal period.

The merchants in Echizen initially required craftsmen to build storage in their warehouses for their goods. Craftsmen also found work building Buddhist temples and altars, of which there were many in the temple district in the city. As the populace grew prosperous, the demand shifted from warehouse-related storage to home storage. That trend has remained, and today, the traditional crafts of Echizen are widely known and highly regarded all across Japan. In addition, Echizen flourished as an artisan place as all of its traditional crafts were complementary and interconnected.

My 2-day adventure in Echizen started at Takefu Station, the main station serving the city center, and from where I set off on a hands-on tour of the city's traditional crafts. It was a trip filled with lots of activities and first times, and one that I would recommend to those who enjoy craft and making things.

Day one

The plan for my first day in Echizen was to check out the city center on foot, visit a woodworking studio that specializes in making dressers (tansu) and head to the knife village to see the blacksmiths working at the forge.

I arrived at Takefu Station in the late morning and set off from there to check out the city. It was a short five minute walk to Kuranotsuji, an area where white-walled warehouses line the street. During the feudal period, Echizen was along the trade route that connected Kyoto and the north along the Sea of Japan side. These warehouses that have remained standing, were where merchants stored their goods. I saw some traditional warehouse design, and more interestingly, the bars and restaurants that have now taken up residence inside.

My walk continued through to Teramachi, a small district, which was modeled after the streets of Kyoto. Teramachi was constructed over 400 years ago and contains about 20 temples. I walked down the cobblestoned main street, Teramachi-dori, and saw the temples co-existing side by side private residences. It was a very peaceful pre-lunch stroll, and I also took some time to visit the temples along the way.

For lunch, I went for volga rice, a local dish consisting of deep fried pork cutlet placed on top of Japanese omelette rice and served with a generous amount of demi-glace sauce. There are a number of places serving this unique dish, which was invented about 30 years ago. I went to Cafe de Imari, which is said to be one of the founding restaurants of volga rice. To get there, I picked up my rental car from the station and drove for about ten minutes.

After that filling lunch, I drove to my next stop, Kicoru, a woodworking atelier. The business has a history of about 100 years, and specializes on combining traditional woodworking techniques and different kinds of wood to create personalized furniture. Inside, I had the opportunity to see Oyanagi-san, the fourth generation artisan, at work.

In the past, there were craftsmen for each stage of making dressers, e.g. blacksmiths produced the nails and metal trimmings, lacquer artists provided the lacquer finishes for the wood, and carpenters cut the wood down to size for assembly. Thus, I found it astounding to learn that all of the parts were handmade by Oyanagi-san, from cutting the wood to sanding down the metal trimmings to the lacquer finish.

A handmade wooden dresser is a collaboration between the artisan's skills and the customer's requests, and one is made to last for a long time. Visitors to Kicoru can expect high quality products that can be passed down from generation to generation.

Moving on, I made my way by car to Takefu Knife Village, a village where different blacksmiths forge blades under the same Echizen Hamono brand while maintaining their own name. The sizable forge is located in the outskirts of Echizen City due to the noise level generated by the machinery and surrounded by rice fields.

The history of Echizen Hamono or Echizen blades started over 700 years ago, when sword smiths from Kyoto found good water, which was necessary for forging blades and tools, in Echizen. Towards the end of the feudal period, Echizen grew to be the largest producer of the farming sickle domestically. Thanks to the high quality of these farming tools, the Echizen brand enjoyed a good reputation and become widely sought after in Japan.

My visit to Takefu Knife Village started with mini tour at the viewing platform on the second floor. The platform provides an overhead view of all the different aspects of knife making, from shaping and hammering carbon and steel, all the way to sharpening and finishing. A characteristic of Echizen blades is that the blacksmiths create their knives from start to finish. No part is delegated nor outsourced to others, which meant that everything is handmade by the people I saw working in the forge.

One of the things I was looking forward to at Takefu Knife Village was participating in one of their activities. There are a number to choose from, and I went for the sharpening activity as I was a little short on time and thought that a sharpening skill would also come in handy at home.

The activity took place in the annex, and there I met master sharpener Totani-san, who led me through the activity. Not only is Totani-san a skilled knife sharpener, he is also the creator of the unique chiffon cake knife, which has earned rave reviews both in the domestic and international cake scene. Under my teacher's watchful eyes, I sharpened my knife on whetstones till it was shop ready and slicing paper like it was butter.

Before I knew it, the sun was starting to set, and it was time for me to head on out. For dinner, I went to Shikura in the Kuranotsuji area in the city center. As I was staying in the city center, I left my car at my accommodation and walked to the restaurant. Shikura is a traditional restaurant serving up affordable kaiseki multi-course meals that include local and seasonal ingredients. It was a great meal of high quality, and I didn't want my dinner to end.

I had heard that the streets in the temple district were quite nice in the evening when the streetlights come on, and I went for a short post-dinner walk to that area. I had a nice stroll down the quiet streets and made my way back to my hotel for the night.

Day two

I started my day bright and early at the Urushi no Sato Kaikan, a lacquer gallery and shop where I would learn more about lacquer. Echizen used to be a major lacquer sap harvesting area with many skilled harvesters who made cuts in the lacquer trees using Echizen blades. These lacquer harvesters would also sell their tools when they went farther afield, further promoting the Echizen brand. It was interesting to know that it takes about 20-25 years before a lacquer tree can be harvested for its sap, and even more remarkably, a lacquer tree would only produce up to 200 centiliters of sap in its lifetime! That is not a lot of lacquer per tree, which explains why lacquerware can go for such high prices.

The high quality of Echizen lacquer meant that it was highly sought after and valued. For example, it was used in the construction of Nikko's Toshogu, a lavishly decorated shrine complex north of Tokyo.

The museum has dioramas made of local Echizen washi paper showing the process of creating lacquer products. They demonstrate the many different craftsmen and a lot of effort were needed in the creation of a single bowl. Simple, unadorned lacquered wooden cutlery is what most people purchase, and the main product for most lacquer artisans. However, detailed and elaborate lacquer works can also be seen at the gallery. In the feudal period, such works were typically commissioned by aristocrats and ruling members of society, the most common being surface paintings on ceilings and doors, and important buildings.

After checking out the gallery, I had the opportunity to participate in a chinkin activity, in which gold powder is spread on carved lacquerware to create a design. My teacher was Yamamoto-san, who is an expert with over 50 years experience. I picked a lacquered plate, drew my design on paper before transferring it on. From there, the real test of skills began: carving the design out using the special chinkin tool which resembled a long lead stick with a flattened end. After I was done carving, the next step was spreading gold powder and finally polishing the plate to remove excess powder. It is advised not to touch the design for at least a day to let it dry completely. I remained patient during my trip, but showed it off to my friends when I went home.

For lunch, I drove to Echizen Soba no Sato, a large soba noodles center which consists of a restaurant, a shop selling soba noodles and local products, and an activity center. Echizen soba is a local delicacy and is typically served cold in a large bowl topped with grated white radish (daikon), sliced spring onions and shaved bonito flakes (katsuobushi), and with the dipping sauce (tsuyu) poured over it.

Instead of heading to the restaurant for lunch, I had made reservations for making soba at the activity center. The activity center is large enough to accommodate large tour groups, but individual participants are also welcome. My instructor took me through the steps of making soba, starting from mixing the flour with water, to kneading and rolling it out, and finally slicing my handiwork. It is worth mentioning here that the massive soba-kiri knives are proudly Echizen blades as well.

The soba I made was brought to the kitchen and cooked, and that was my lunch. Afterwards, I took some time to walk around the place, checking out the soba factory where the machine-made soba is produced. I also made sure to sample the soba soft serve at the shop and can report that it was absolutely delicious.

The last Echizen traditional craft on my list was Echizen washi, traditional Japanese paper. I had already seen the local washi used at the different places I visited before, and this time, I was going to learn how it is made. I started my washi education at Okamoto Shrine, the only shrine in Japan dedicated to the god of paper, and paid my respects there. The main hall at the serene shrine has a unique overlapping roof design and lots of intricate wood carvings, making it an interesting place to see and a quiet place for contemplation.

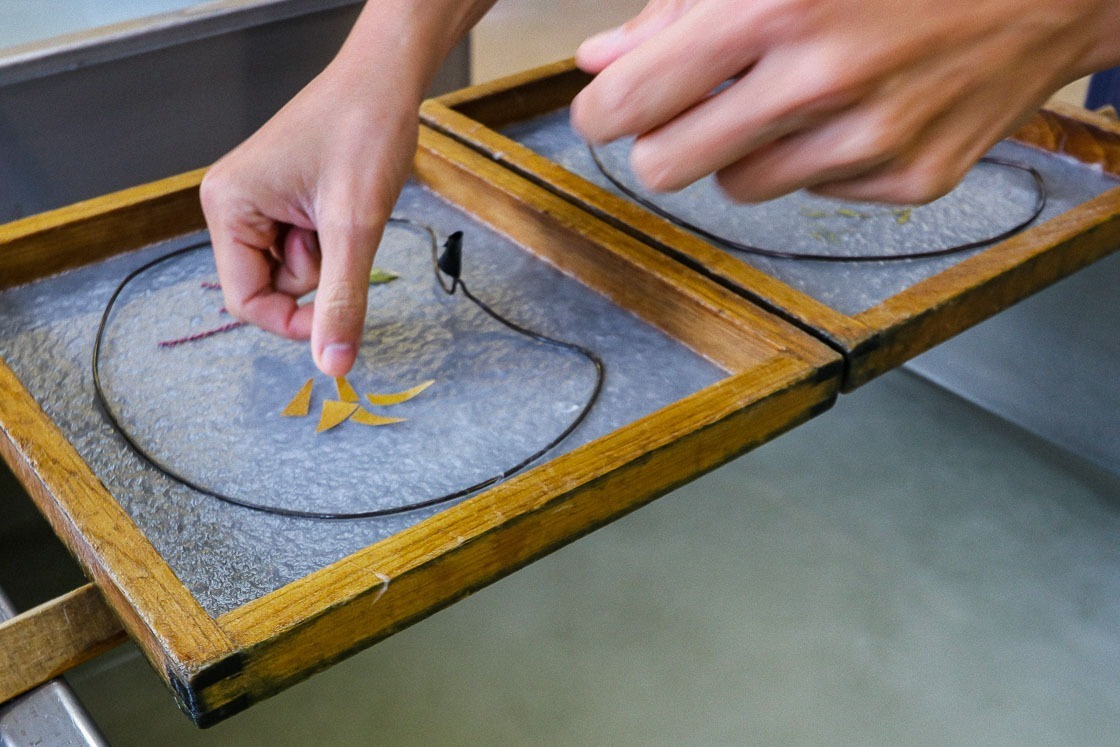

From there, it was off to the nearby Echizen Washi Village, where I headed to the Udatsu Paper and Craft Museum first. There, I saw locals sorting and cleaning the tree bark that was to become washi. The museum is also an operating washi mill, and I had a first-hand look at how washi was made. It is a labor intensive task as everything is done by hand, the traditional way. Needless to say, the quality of Echizen washi is very high, and washi here is customized to the client's requests.

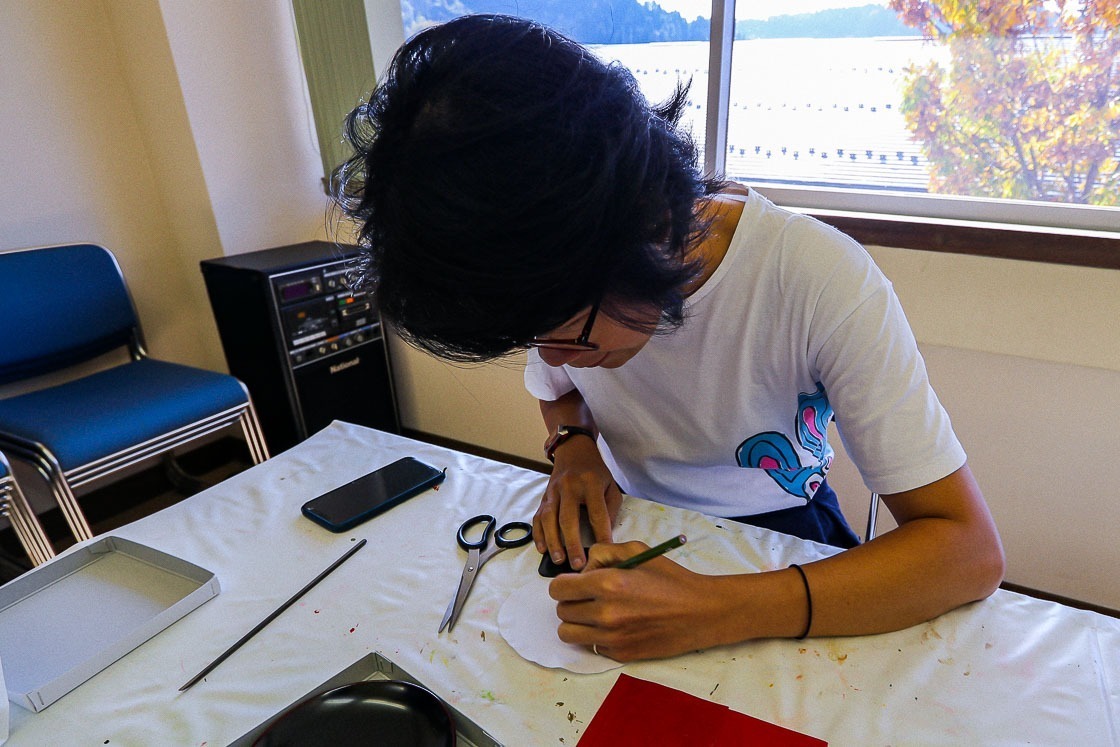

Next, I went to Papyrus House, an activity center and shop, just across the road. After seeing how washi paper was made, it was time for me to make my debut. There were a number of washi making options, and I went for making a hand-held washi fan (uchiwa). My activity took about 20-30 minutes, and started off with scooping up the paper fibers using a traditional rectangular sieve. Then, I added decorations to the wet paper fibers before using a special vacuum to dry my paper. All that was left to complete my work of art was to stick the paper on the fan and let the glue dry.

The shop and other washi businesses in the Echizen Washi Village sell a wide variety of washi paper and washi products. It was interesting to see the different designs, but all I could think of was all the hard work that goes into making a single sheet of paper! I am sure that in the 30 minutes it took for me to make a small fan, a washi artisan would have already processed at least ten large sheets.

With that, my trip to learn all about the traditional crafts of Echizen had come to an end. My backpack was full of souvenirs: the knife I sharpened at Takefu Knife Village, the chinkin lacquered plate with the gold powder design I carved, and the Echizen washi uchiwa I made. I also had a great time learning about the history of the traditional crafts, and of how they are independent trades yet interconnected. All in all, I had a great trip, and one I wouldn't hesitate to add to a travel itinerary along the Sea of Japan.

Access

Takefu Station on the JR Hokuriku Line is the main station serving Echizen City.

The city center is within walking distance from the station, but all of the traditional craft places are between a 20-30 minute drive from there. As public transportation is fairly limited, a rental car is recommended for getting around, or a rental bicycle for those who are more outdoorsy, or a taxi. Rental car outlets, rental bicycle shops and taxis are available near Takefu Station.

How to get to Takefu from Tokyo

Take the Tokaido Shinkansen from Tokyo to Maibara, and transfer to the Shirasagi limited express train to Takefu. The one way journey takes around three hours and costs about 14,500 yen for reserved seats on both legs, or 13,800 yen for unreserved seats.

How to get to Takefu from Osaka or Kyoto

Take the direct Thunderbird limited express train from either Osaka (100 minutes, about 5500 yen one way) or Kyoto (around 70 minutes, about 4500 yen one way) stations to Takefu Station.